The nightmare of Nazi victory two decades on: German plans for Europe

Confident of their victory, the Germans drew up plans for how the post-war world was to be organized. According to Himmler’s nightmarish project, there would eventually be 400 million Germans living between the Atlantic and the Urals. This would have meant an apocalypse for the Poles and other Slavic peoples.

Jakub Ostromęcki

Gunther Van Drunen, a 45-year-old veteran of the “Nederland” 23rd SS Panzergrenadier Division, was already used to news of the arms race being fueled by the Jewish lobby at the White House. He was fed up with articles explaining the difficult economic decisions that the now aging chancellor had to take in response to that threat. After all, the former SS officer wrote such pieces himself. During the capture of central Leebhaven (formerly Leningrad) 25 years earlier, he had almost lost a foot. Discharged from the army, he discovered a talent for writing during his convalescence, and became a journalist for the Dutch edition of the newspaper Völkischer Beobachter.

Van Drunen, who fulfilled all of the racial requirements as a representative of one of the Germanic nations, had been a citizen of the Reich for many years. A similar honor was bestowed on well over ten million Dutch, Flemings, Danes, Norwegians and Swiss who were decreed to be German. The category even included a few French, who by some miracle had survived the centuries of effeminacy and decadence absorbed from the Paris court.

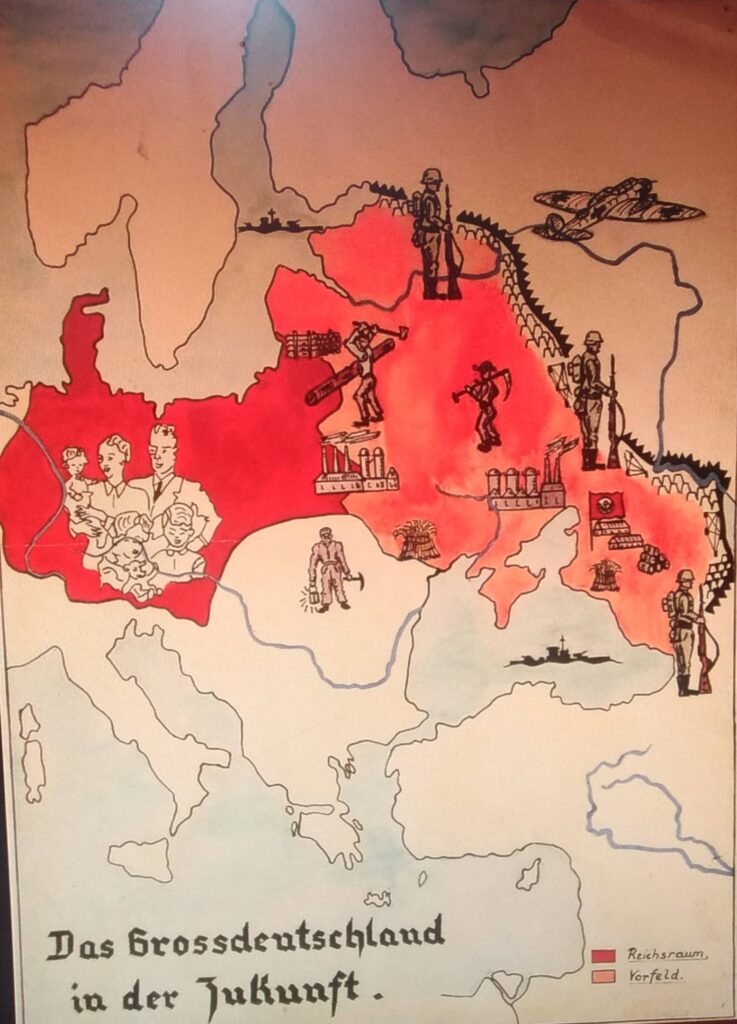

The world in which Gunther lived was the fulfillment of the dreams of the German conquerors. Switzerland had turned out in the end not to be an unconquerable fortress, and had been divided between Italy and the German Reich. The French were left with their satellite state with its capital at Vichy, naturally deprived of their colonies. Brittany was also granted autonomy, although it was the home of Kriegsmarine bases and the Luftwaffe’s rocket launchers and high-powered radar stations. The greater Reich in the west reached from the Bay of Biscay to the Arctic Circle in Scandinavia. In the east, in Siberia, the 70th meridian marked the border with Japan. Germany controlled Afghanistan. The Mediterranean had been handed over magnanimously to Italy, but sub-Saharan Africa was a German colony.

Gunther had disliked the arrogant English since childhood. He had books at home recounting the triumphs of the Dutch fleet in the seventeenth century and the later humiliation of the merchant republic. He was thus pleased by Britain’s defeat and the installation of a puppet government there. Meanwhile the centuries-old dream of the Irish had come true: thanks to the Reich, they ruled over the whole of the Emerald Isle.

Great politics was not what was currently on the veteran’s mind. In his apartment in the working-class suburbs of Rotterdam, methodical preparations were being made. His wife and children were packing their cases. Gunther was leafing through the phone directory for firms specializing in long-distance removals. He still had to put his papers in order and secure his latest acquisition – a new electric typewriter. It had arrived not long ago by mail. The box featured the logo of the Steyer-Radom factory. It was magnificent, and he had bought it astoundingly cheap. A newspaper colleague told him that the factory’s management could be proud of their low labor costs…

Twenty years after the war

Gunther was setting off for the east, to take over a farm in Ukraine, which he would receive free of charge. Of course, he would not have to work the land himself. As an SS veteran, he was to become a Wehrbauer – a soldier-farmer. The work on his 100 hectares or so of land would be done by Ukrainian peasants deemed suitable for Germanization. During his journey, the veteran intended to write a book called A Journey to the German East 20 Years after the War.

The colonization of the land to the east was proceeding with some resistance – the people of Swabia, Baden, Bavaria, the Rhineland, and indeed the Netherlands felt too comfortable on their own land to want to embark on a new adventure. The sole incentive was free land and up to 20 years’ tax-free status. Only the threat of American B-52 bombers persuaded many to emigrate to the safer interior.

Gunther and his family drove through the old Reich along one of the newly built freeways. The effects of Anglo-American bombing were still visible in places, but overall the country made a fine impression. The mentally or physically disabled were absent – the former SS man knew that this was due to a harsh but necessary policy that forbade the mentally ill to reproduce. There was no place for the weak in the Germanic race. The parents of disabled children were asked directly whether they would submit their offspring to therapy that carried a high risk and little chance of success. According to the newspapers, most of them consented. There was therefore no cause for grieving.

Nor did Van Drunen grieve over the Catholic Church. Since the end of the war, the Reich had allowed no new building of temples to the idol of the desert who was foreign to the Germans. It had had enough of the impudence and stupidity of people like the bishop of Münster, von Galen, who criticized the chancellor for his supposedly immoral policies toward the sick and for destroying the “traditional” family. In the times when the Reich was spilling blood in the struggle with Bolshevism, von Galen had been undermining it. It was therefore a good thing that he had finally been sent to prison, where he died soon after.

The veteran liked the way the Reich was ensuring population growth following the wartime losses. While Heidi was Gunther’s wife, she was not his only woman. He had another five children from other relationships. Their mothers received generous welfare from the state. They were pampered in return for their service to the nation and the race, and woe betide anyone who referred to the children born outside marriage as bastards. Other old-fashioned women who felt bourgeois pangs of conscience about their illegitimate children could always submit a declaration that the father had died at the front. Such a woman was then given a wedding to the dead soldier, and from that moment on would be treated by those around her as a respectable widow, naturally assisted by government welfare. Gunther accepted that this was not a time to stick rigidly to the Judeo-Christian vision of the family.

In the Netherlands that he had left behind, and in the rest of the Reich, there were no more Jews. It was due to a Jewish bank that his father’s shop had once gone bankrupt, and they were also among the Bolsheviks that he had fought in Russia. Apparently they had been exiled to somewhere in distant Siberia to separate them from the Aryans – after all, they spread diseases. Apparently some of them had died, but that was their own fault. It didn’t actually matter much to Gunther.

Instead of the Jews, he preferred to admire the bridge over the Elbe in Hamburg that was larger than the one in San Francisco, and the museums in Scandinavian Trondheim and Prussian Königsberg, with their collections of works by German masters that had been jealously hidden by countries that now no longer existed.

The Third Reich’s plans

Of course, Gunther the war veteran did not really exist. However, the above introduction is not entirely an alternative history. The plans of Hitler and Himmler regarding the organization of the greater German Reich and agricultural settlement in the east are quite well documented. Had the Third Reich won World War II, these dreams might well have become a reality. The subject of the Nazi state’s geographical ambitions and future system of rule is presented in accessible form by Gerhard L. Weinberg in his book Visions of Victory. The Nazi social revolution described there was to take place in stages. German society in the 1940s was not ready for the new vision of the family propagated by the SS. Therefore, during wartime, the above-mentioned cases of weddings with dead soldiers required the presentation to a court of letters and witness testimony confirming that the deceased had indeed loved the pregnant woman and wished to have children with her. Only then could such a woman obtain the right to welfare. In turn, the T4 campaign is described in detail by Götz Aly in his book The Incriminated: “Euthanasia” 1939–1945. During the war, protests by the Catholic Church meant that the Third Reich had to conceal its campaign to murder the mentally ill. “The Führer wants to have peace in the country,” Goebbels noted in his diary.

Consequently, from 1942 onward such patients were not murdered in gas chambers, but were secretly starved or injected with poison under the pretext of receiving treatment. However, it was not intended that bishop von Galen should get away with his protests. Goebbels concluded: “The Church question will be resolved after the war in one fell swoop.” This simply meant the de-Christianization of the old Reich. The devious effort to erase from the Germans’ consciousness the genocide committed by their leaders was summed up by Rommel’s biographer, American military intelligence officer Charles F. Marshall. He was referring to the wives of military officers, but his point could also be applied to the rest of society: “They knew enough to know that they did not want to know any more.”

(By Dralon – Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=914248)

Two decades after the war, central and eastern Europe would have looked completely different from before the start of the conflict. Generalplan Ost would have been implemented to its maximum and most terrible extent. That plan, basically a whole series of directives, circulars and expert opinions, began to take shape as early as 1939. On November 25 of that year, Ehrard Wetzel, an expert at the Nazi party’s Racial Policy Office, drew up a document titled “The matter of the treatment of former Polish areas from a racial policy viewpoint.” This concerned mainly the Polish territories that had been incorporated into the Reich. However, plans for the whole of central Europe were soon made ready. They were thought up at the SS Race and Settlement Main Office (RuSHA). This subject has been researched by Czesław Madajczyk, and one of the most famous studies of the fate that awaited the whole of Europe under the rule of a victorious Reich is the work by Isabel Heinemann, Race, Settlement, German Blood. The SS Race and Settlement Office and the New Racial Policy Order of Europe.

Had the insane plan come to fruition, the Poles would have been a pauperized, mostly degenerate diaspora living in small clusters from the Atlantic coast to the Urals. Eighty percent of ethnic Poles – around 20 million people – would have disappeared from the territory of the former Second Polish Republic. Specifically, referring to the reality of the occupation, from the lands incorporated into the Reich, the General Government, and parts of Reichskommissariat Ostland and Reichskommissariat Ukraine. The intelligentsia, social activists, leading entrepreneurs, politicians, and intransigent bishops would be sent to concentration camps or taken into the forest and shot. Most of the expelled population would end up in western Siberia, near the border with Japan.

Commenting on the ideas of his boss, Heinrich Himmler, Wetzel proposed an alternative plan that would have been more lenient from our point of view: “Brazil, with its capacity […] is in urgent need of people. […] Transferring millions of Poles who are most dangerous to us, by way of emigration […] to Brazil does not seem impossible. […] However, for the largest part of the racially undesirable Poles, consideration should be given to resettling them to the east.” The exodus of Poles across the Atlantic to Brazil would have had to take place with the agreement of the United States or after the defeat of its navy. It would have been a difficult task, and we can easily imagine the perverse propaganda posters on the streets of occupied Polish cities: “The Jewish regime in Washington obstructs Polish development!”

Destined for Siberia alongside the Poles would have been 50 percent of Czechs, 65 percent of Ukrainians, and 75 percent of Belarusians. Many Ukrainians were to be settled in the eastern part of the General Government, where they would have received privileges over the Poles, as illustrated by events in the Zamość region in 1943. Of the Poles expelled from that region, 21 percent were meant to end up in the crematoria of Auschwitz and Majdanek. This was a kind of pilot program for the remainder of the General Government, and no doubt the same ratio would have been applied following a German victory in the war.

The end of the Poles

What fate would have awaited the Poles who remained in the lands incorporated into the Reich and in the General Government? This question was answered by Hitler in a conversation with Martin Bormann, who recorded on October 2, 1940: “The German worker must be given the opportunity to rise to a higher level, which in the case of the Poles does not enter into consideration. The General Government should in no case become a closed and uniform economic area which itself produces fully or partially the industrial goods it needs, but is to serve us as a reservoir for basic labor: brickyards, road building. Nothing can be made of the Slav other than what he is by nature.” The Poles in the Zamość region served additionally as farmhands and agricultural workers for German settlers.

There was a vestigial legal Polish school system in the General Government. There were no lessons in history, geography or physical education, and teaching of the Polish language was reduced. Due to poverty, lack of transport, winter closures of schools, the commandeering of buildings by the military, and a shortage of teachers, the number of children attending these schools was a mere 20 percent of the 1939 figure. In the final years, teaching took place once a week. Of course, we do not know what the situation would have been following a German victory, but Himmler had said that it was enough for Poles to be able to count to 500. There would no doubt have also been vocational and agricultural schools, but largely for fee-paying students.

The lands of the General Government inhabited by the remaining Poles would therefore have been a country where a foreign traveler would be gazed upon by haggard, undernourished, mistrustful natives. Due to the murder of the elites and the fact that the atomized group lacked its own institutions, all types of pathological phenomena would become commonplace, including alcoholism, and a lack of respect for work and property. Agricultural land there would have been much less fragmented – German settlement required large farms.

In place of the Poles who had been murdered or expelled, millions of Germans would arrive. According to Himmler’s plan, there would eventually be 400 million Germans living between the Atlantic and the Urals! Like in the story of Gunther, rich farmers from the Rhineland, Baden, Swabia and Bavaria would have been none too keen to set off for the wild east, and so Germans would have been brought there first from the Baltic countries, Volhynia, Bessarabia, or Dobruja.

The areas settled by them would appear on the map as large strips. One of these would run from Nowy Tomyśl to Łódź. There, one branch would lead toward Ciechanów and another to Częstochowa, forming a cordon separating the western lands from the several million Poles and Ukrainians in the General Government. A second, smaller strip would pass through Sępólno Krajeńskie, Bydgoszcz, Chełmno, and Grudziądz. Another would run along the Narew river to Suwałki. More than a half of farms would belong to Germans, and the remainder to Poles working in “servant villages.” “We are Germanizing the lands, not the people,” Hitler reiterated. However, the needs of war made it necessary to Germanize some of the Poles. There would have been slightly more of them left in Western Pomerania and Silesia, because the gauleiters there, Forster and Bracht, wanted to deprive Poles of their national identity rather than expelling them. In some districts, between 80 and 90 percent of the population was entered on the third and fourth Volksliste, meaning that they were persons of German origin who had become integrated with the Poles before 1939 or regarded themselves as Poles.

Of the aforementioned 80 percent of expelled Poles, a certain number would have ended up in the Reich. These would have included forced laborers and people from the third and fourth Volksliste. Those taken to the Reich would also have included Poles who were “suitable for Germanization,” having “appropriate racial features.” The Polish doctor Józef Rembacz, who was sent to work at the RuSHA camp in Łódź, described the racial selection procedures in his memoirs: “Examinations were performed to assess posture, weight, build, skull shape, face width, size and spacing of eyes, eye and hair color, and hair thickness. On the basis of this, an appropriate racial assignment was made. These examinations were carried out by specialists in matters of race, known as Eignungsprüfer – selectors.” The assessment procedure was in fact applied to Germans from the first and second Volksliste, but this original formula could also have been used to classify Poles.

The drama of the children

Another wartime phenomenon was the Germanization and kidnapping of children. In a document titled “Some thoughts on the treatment of foreign tribespeople in the east,” Himmler wrote: “If we recognize such a child as our blood, then its parents will be informed that it is to go to school in Germany and to remain in Germany permanently. No contact with its parents. The parents of such a child of good blood will be given a choice: either to give up the child – then they will presumably not produce any more children and there will be less danger that through such people of good blood the eastern nation of subhumans might gain a new class of leaders who are dangerous to us and equal to us; or else those parents will agree to go to Germany and become loyal citizens of the state.” As the stories of those children show, it was among them that Germanization would have achieved its greatest successes.

Poles in the “old Reich” would have lived in very different ways. Forced laborers wore special badges with the letter P, and were not allowed to leave their living quarters or to maintain close relations with Germans. Those designated for Germanization had identity and travel documents and the same food rations, earnings and welfare rights as other Germans. The destiny of such Poles is well illustrated by the story of the Jasek family, as recounted by Heinemann. They lived with a rich farmer, Ulrich Senf, in Mehrow close to Berlin. At Christmas their host presented them with candles “so that they could celebrate the German tradition under a lit-up Christmas tree.” Such “fraternization with Poles” angered the local Nazi party branch. Senf, who according to the law regarded the Jaseks as Germans, wrote a complaint to Otto Hofmann, head of one of the RuSHA units.

Also to be found in the Reich would be some Poles who had lived in France, and who by the Nazis’ twisted logic were recognized as racially valuable. They were granted German citizenship without much fuss, and without being asked their view of the Third Reich’s political system and conquests.

Perhaps a looming defeat would have caused the Soviets to release a far greater number of Poles from the labor camps in 1941. Like those who in reality were saved under the command of General Władysław Anders, they would have left the Soviet Union before the Germans arrived. Had Britain been defeated, they would have had to escape from the Germans and the Soviets not to the Middle East, as happened in 1942, but probably to India. There they would no doubt have lived as émigrés, hoping that the United States, needing people to fight against the German Reich, would send a fleet to collect them. Among these exiles would have been many intellectuals, and this would no doubt have been the last true bastion of the Polish nation.

This article was first published in Polish in the Historia Do Rzeczy monthly in September 2023