The Devils’ Alliance. The evil coalition of Hitler and Stalin against Poland (Part 1)

The Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact paved the way for the outbreak of World War II. The tactical alliance of previously mortal enemies developed into a close coalition. However, in order for this to happen, Poland, who stood in their way, had to be destroyed.

Grzegorz Janiszewski

After the Anschluss of Austria, the situation in Europe began to resemble a rollercoaster. Stalin expected that an armed conflict would arise sooner or later but had no intention of allowing himself to be drawn into a war in defense of the Western Allies. Hitler was ready to move away from the previously implacable anti-Bolshevism. The key issue was how to play the Polish authorities, who were trying to maintain an equal distance to their neighbors. Two international crooks had to come to an agreement on this issue, even if they were to leap at each other’s throats soon after. Pilots of the Condor Legion were still bombing Soviet advisers and Moscow-supplied equipment in Spain when Stalin and Hitler began to plan their alliance1.

On March 10th, 1939, Stalin made his famous “chestnut speech”2 assuring that the USSR was ready to make a deal with any state, regardless of its political system. He contrasted the Third Reich to Western democracies, which he accused of inciting war with Germany. Marshal Voroshilov presented forecasts which showed that France and Great Britain would not be able to meet Germany’s force.

Devils’ Alliance

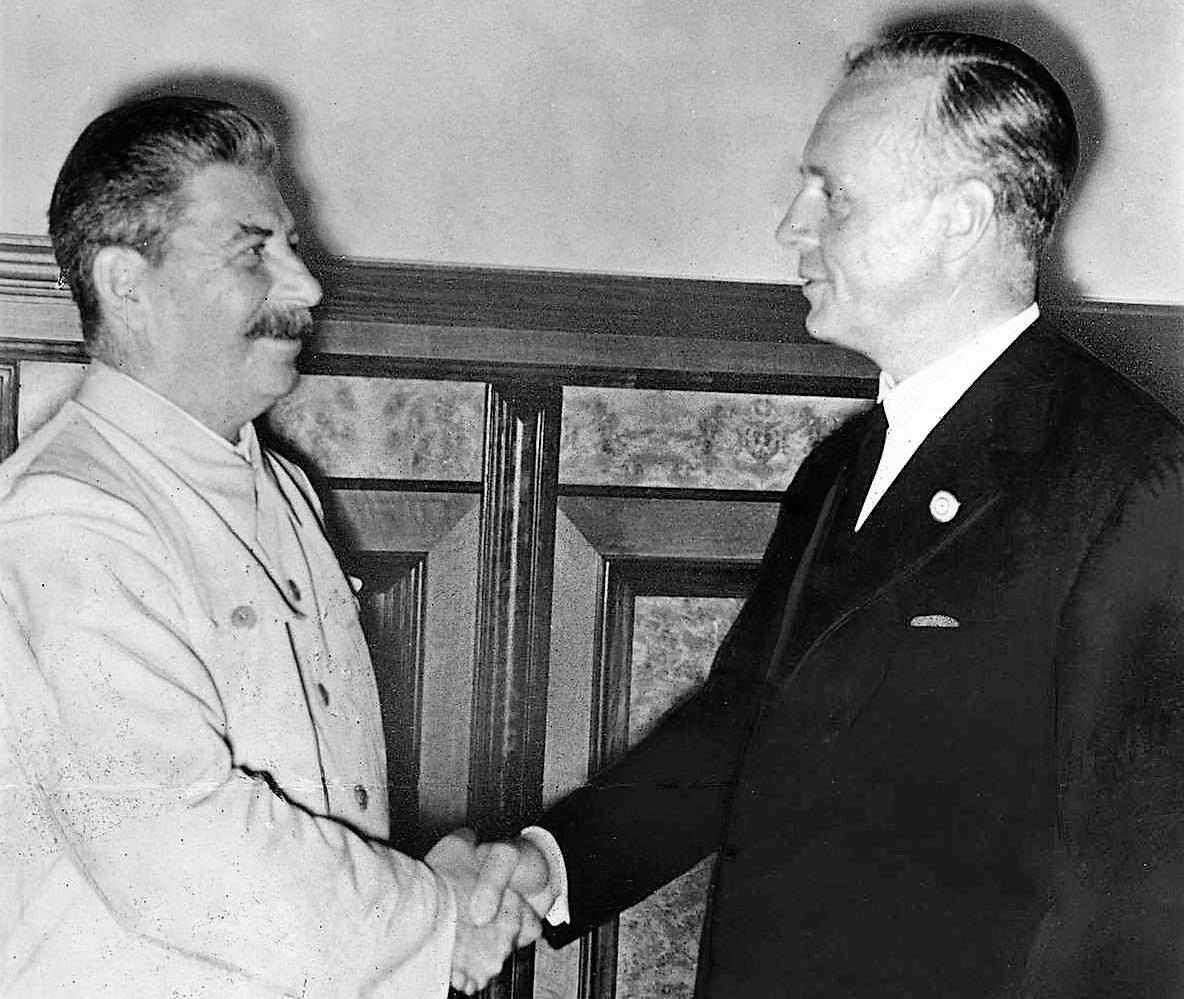

The calculation became simple and the road to an alliance open. It was only necessary to replace the opponents of the cooperation in key positions – in the post of People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, the Jewish Litvinov was replaced by Molotov. Immediately afterwards, work on the pact started in full swing, albeit in secret. Stalin broke off negotiations with Western states only when, in August 1939, Hitler agreed to give him half of Poland, part of Latvia, and Estonia. On August 23rd, Ribbentrop flew to Moscow to sign the treaty.

After the final arrangements, Stalin gave a modest party, at which, instead of champagne, which he was not a fan of, toasted Hitler’s health with a glass of vodka. On the news of signing the pact, he started running around his office, thumping the walls with his fists and exclaiming that he had the world in his pocket. The “Devils’ Alliance” had entered into force. The fate of Poland was sealed.

The pact consisted of just seven articles which, when made public, caused global consternation. However, the real ticking time bomb was the secret supplementary protocol, regulating the “spheres of influence” from the Baltic to the Black Sea, de facto establishing the limits of looting in the event of war.

Blows from both sides

Immediately after the German aggression against Poland, a group of Soviet officers headed by General Maksim Purkayev came to Berlin. Direct communication was established between the Wehrmacht and the Red Army.

Four hours after the attack, the Germans turned to the Soviets for military assistance. The need became even more pressing after the Western Allies declared war on Germany. Hitler hoped that the Red Army would relieve the weight from Wehrmacht’s soldiers, and that part of his forces could be transferred to the west. Stalin, however, stalled. Units were mobilized near the border with Poland and large maneuvers were launched as part of the aggression plan. Lavrentiy Beria set up special operational groups with the NKVD, which were to enter Poland first. On September 9th, Molotov informed the German ambassador that the Soviets would move in a few days. Five days later, the Polish government finally collapsed. Stalin did not solely wait for the outcome of the Wehrmacht campaign in Poland. The decision to march in was made after receiving intelligence about the results of the conference of the Western Allies in Abbeville on September 12th. France and Great Britain decided there that they would not come to Poland with armed help3.

Finally, on the night of September 17th, Stalin, Molotov, and Voroshilov informed the German ambassador Schulenburg that the Soviets would be entering Poland within hours. The latter still had time to amend the Soviet note informing about the intervention, which the Deputy People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs Potemkin tried to hand over to the Polish ambassador at around 2 a.m.

An hour later, Poland’s eastern border was crossed by 8 Soviet armies, totaling over 600,000 soldiers, 4,733 tanks, and 3,298 airplanes. Poland, attacked by two neighbors of immense power, did not stand a chance. After September 17th, the surprisingly strong morale of the Polish army began to collapse. They previously loyal conscripts of Belarusian and Ukrainian origin began to desert en masse. Upon the news of the Soviets entering and leaving the country by the Commander-in-Chief, the commanders disbanded their troops, seeing no chances for any further resistance. The campaign against Poland ended with the German-Soviet parade in Brest, Belarus on September 22nd. The marching units from the honorary tribune were greeted by Generals Heinz Guderian and Semyon Krivoshein.

(…)

This article was published in 2021 in Do Rzeczy magazine.

1 The Condor Legion was a unit from the Nazi Germany air force which supported the cause of gen. Franco during the Spanish Civil War from July 1936 to March 1939

2 The term “chestnut speech” comes directly from the words of Stalin, who said that he would not allow the Soviet Union “to be drawn into conflicts by warmongers who became used to others drawing chestnuts out of the fire for them”.

3 The first sitting of the Anglo-French Supreme War Council took place on September 12th, 1939 in Abbeville, France between the Prime Ministers of France and the UK – Edouard Daladier and Neville Chamberlain, respectively. The Supreme War Council decided not to launch a general land offensive on the Western Front and RAF air operations over Germany. This was a breach of obligations under the existing alliance agreements – the military convention to the Polish-French alliance (obliging the ally to a supportive attack within fifteen days of announcement of the mobilization) and the Polish-British treaty of August 25th, 1939.