Siberian Exile in Polish History (Part 1)

Russian terror against the Poles reflects Moscow’s fear of freedom which has been Poland’s organizing principle in the Eastern Borderlands of Western Civilization.

Marek Jan Chodakiewicz

There has been a horrific continuity and consistency in Russia’s approach to her own people and neighbors. For several centuries now the Kremlin has resorted to deportations as a means of control and enforcing its will. The victims have been manifold and the denizens of Poland prominent among them. Russian terror against the Poles reflects Moscow’s fear of freedom which has been Poland’s organizing principle in the Eastern Borderlands of Western Civilization, which also happen to be Russia’s eastern peripheries. We would like to explore briefly the history of the deportation mainly of the Poles, but also others.

In the Polish lore, to be transported to “Siberia” (na Sybir) can refer anywhere in the lands under the Muscovite, Russian, or Soviet control in the past 500 years. The Poles usually refer to the victims of such deportations simply as “the Siberians” (Sybiracy). Scholars have tended to focus on the mass exile during the Soviet times, in particular Stalin’s rule. However, we shall also consider earlier deportations. Basically, throughout history, any conflict with Russia invariably resulted in the deportations of Poland’s citizens to the east. The process commenced in the mid-15th century because of the Lithuanian connection and continued unabated until the second half of the 20th century. It is a legacy of about half a millennium of deportations. A whistle-stop history of Poland is in order to understand the Polish encounter with Siberia.

In the 14th century the Grand Duchy of Lithuania acquired the bulk of the territories of Ruthenia (Rus), including the defunct Principality of Kiev, which had been conquered and destroyed by the Mongols. Most Ruthenian principalities in the west and south-west united rather willingly with the Lithuanians. Others continued apart. However, one eastern Ruthenian principality, the Duchy of Muscovy, became actively hostile. It attacked its other Ruthenian neighbors and absorbed them. It also fought with Lithuania over the inheritance of Kiev. Until the middle of the 17th century the Lithuanians had the upper hand, in particular because they enjoyed the support of the Poles. The latter inherited Lithuania’s Muscovite problem after the Grand Duchy entered into a personal union with the Kingdom of Poland at the end of the 14th century and, then, a federal union in the mid-16th century. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth thus was formed as a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional state. It enjoyed an unprecedented degree of freedom that was practically unmatched anywhere else in Europe until the 19th century. Its system and ideology further exacerbated the conflict with Moscow.

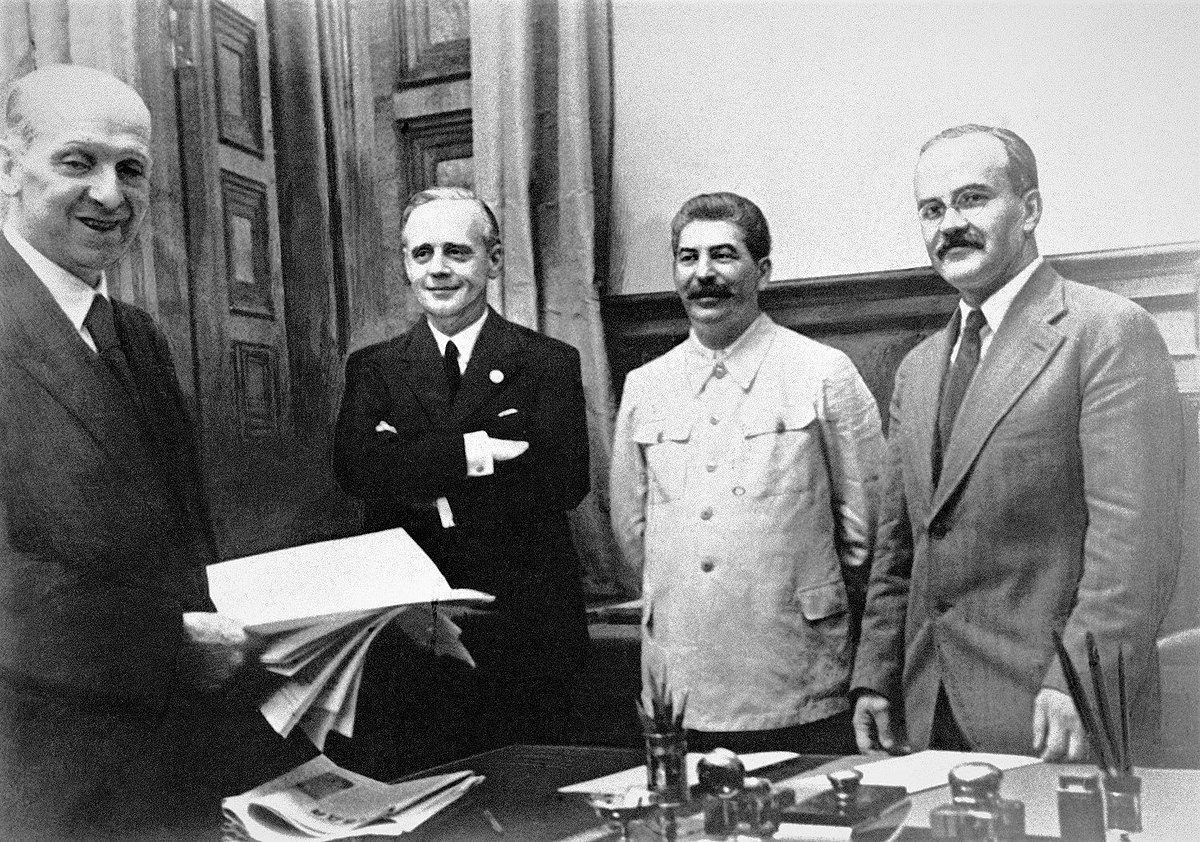

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth successfully opposed the Muscovite imperial expansion to the west until the 18th century. However, it ultimately failed. Incessant warfare continued until the vassalization of Poland-Lithuania and its ultimate partition in the 18th century (1772, 1791, 1795) by Russia with the assistance of Prussia and Austria. The Poles, Lithuanians, and Ruthenians rebelled against Russia and its Tsars in a series of uprisings in the 18th and 19th centuries (1768-1772, 1794, 1830, and 1863) as well as the Revolution of 1905. Later, during the First World War, following the collapse of the Three Partitioning Powers, Poland won her independence. It was soon threatened by a Communist invasion from the east but the Poles defeated the Soviets in 1920. After a short interlude, the USSR pounced upon Poland once again in 1939. This time it was allied with Nazi Germany. Following the collapse of the Nazi-Soviet alliance in 1941, the USSR nearly suffered defeat at the hand of the Third Reich but it eventually recouped and won. The victory meant that Moscow re-occupied the lands of the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and, indeed, the areas up to the Elbe River dominated them until after 1989. It was then that the Kremlin satellite “people’s” Poland freed itself from the Soviet shackles and witnessed other captive nations achieve their liberty.

This framework is indispensable to understand the permanence of “Siberia” in Poland’s collective consciousness. However, dry textbook history alone is insufficient to understand the grip that “Siberia” has in Poland’s collective psyche. One needs to particularize the tale before generalizing.

Siberia: To mid-18th cenutry

Practically every contemporary Pole should know of someone, sometimes a relative, who was in “Siberia.” Many, perhaps 20% of the population, have Gulag victims in their families. Because of mandatory education, most ordinary Poles even realize that the Russian authorities also deported people from Poland in the 19th century. Yet, only very few are aware that forced transportation to the east has a five hundred year long tradition in Moscow’s politics. And it was inexorably tied with the question of slavery.

From its very inception, Muscovy resorted to institutionalized slavery. In addition, the remoteness, poverty, and tyranny of the Muscovite state repulsed talented immigrants. To compensate, the rulers of the Kremlin conducted salve raids for peasants and master craftsmen outside of their realm. The Muscovites simply carried those off from their neighbors and forcibly settled them on their lands. From the middle of the 15th century they also raided yearly the borderlands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania without a formal declaration of war. The Muscovites further reduced Tver and Novgorod the Great. The captives were brought duly to Muscovy. When open war broke out with the Polish-Lithuanian state in 1492, Moscow quickly pounced on Lithuania’s Ruthenian lands, burned several of their principal cities, and kidnapped the people and rulers to the east. Afterward, formal hostilities ceased but informal Muscovite raids continued as before until the official outbreak of a new war in 1499. Once again, the Kremlin attacked and captured a number of major localities subjecting their inhabitants to the standard treatment. A peace concluded in 1503 left those spoils in the hands of the victors, who proceeded apace with their undeclared war. The Kremlin gobbled up the lands to its west one by one. The fall of Smolensk shook the Polish-Lithuanian state from its complacency and led to a brilliant victory over the Muscovites in 1514. Some of the lost Ruthenian territory was restored to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, but Moscow steadfastly refused to return most of the civilian captives and many of the POWs, whom it made into slaves.

Afterward, Muscovy turned its attention elsewhere. A peace of sorts reigned along the Commonwealth’s eastern border until the war over the Baltic provinces (1558-1564, 1575-1582). As always the invaders carried off many captives. For the next twenty years, until the official peace treaty was signed in 1602, Poland-Lithuania vainly pleaded with the Kremlin for their return. Some died; others slaved away at the estates of the Tzar and his nobles; and the remainder suffered exile in Moscow’s newly conquered Siberian lands. A document of 1584 mentions for the first time the presence of the citizens of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth among the Siberian exiles, dubbing them “Lithuanian people” (litovtsi). The Muscovites customarily referred to the Commonwealth as “Lithuania” and to her people as “Lithuanians.” That means that the captives were either Lithuanian, or Ruthenian, or Polish. At least some of them were noble and educated. The first exiles were simply dumped at far away Siberian outposts and left to fend for themselves. The remoteness of the area guaranteed that virtually no escape was successful. Hence, the exiles set up defensive forts, fought against the natives, and ran a Muscovite administration in Siberia. As some linguistic studies show, early “Russian” documents from the region are replete with Polonisms. A few of the deportees defected to the Siberian natives and the Mongols.

More Polish prisoners found themselves in Muscovite chains during the so-called “Times of Trouble” (1604-1619). When Muscovy was gripped by anarchy, a private expedition of Polish-Lithuanian-Ruthenian lords supported a usurper for the throne. Later, the King of Poland involved himself with the affair and the armies Commonwealth briefly occupied Moscow. Soon, much of the occupying force was slaughtered; the survivors were deported. This time the Muscovites seized and transported even the diplomats dispatched to negotiate the prisoner release. Most ended up beyond the Urals, at Tomsk in particular. A few subsequently won their freedom through ransom and diplomatic efforts of the Commonwealth. However, during the negotiations, the Muscovite diplomats claimed that most prisoners had either died or switched their allegiance to the Tsar. As a matter of standard policy the captives were subjected to enormous physical and psychological pressure to embrace Orthodoxy. Their conversion under duress sufficed to become Moscow’s subject permanently. The involuntary converts remained in Siberia forever. Fresh captives also fell into the Kremlin’s hands during the wars against Poland-Lithuania in 1632-1633 and 1654-1655, and the subsequent occupation of the Grand Duchy which lasted until 1660. During the respite in the official hostilities the familiar cycle of the unofficial slave raids against the Commonwealth continued. And so did the official peace negotiations, which included the efforts to secure the freedom of the captives. In 1667 the Muscovites agreed to free some of the nobility, clergy, and soldiery. No peasants were released, nor burghers neither Jews who had accepted Orthodoxy under duress.

There have been no statistical studies of any of those early deportations. According to a single very conservative estimate, 1,500 Polish prisoners were dispatched beyond the Urals between 1583 and 1645. It appears however to be a gross understatement.

In the 18th century the Commonwealth’s incapablity of either triumphant war or successful diplomacy grew exponentially. It became a de facto vassal state of Muscovy, now waxing supreme as the Russian Empire. Foreign armies crisscrossed Poland-Lithuania with impunity and the Russian forces in central and western areas commenced the same tactics of kidnapping people they had practiced in the eastern borderlands for three hundred years. The Muscovites captured and deported the citizens of the Commonwealth with impunity during the Northern War (1700-1721) and the War of the Polish Succession (1733-1738). During the Seven Years War (1756-1763), when busy fighting the Prussians, the Russians nonetheless found time to kidnap Polish peasants and dispatch them to Siberia.

The practice of deportations intensified as the opposition to the Russian rule grew within Moscow’s Polish-Lithuanian satellite. For example, in 1767, after they opposed a law sponsored by the Kremlin, the Muscovites exiled four Polish senators to Kaluga. Other Polish parliamentarians were forced to flee and hide. Moscow consistently and ruthlessly opposed reform; the Poles were incapable of meaningful opposition. This lethal combination of impotent resistance and the vain endeavors to reform itself doomed the Commonwealth. It was duly partitioned between Russia, Prussia, and Austria in three stages (1772, 1791, and 1795). Now, new waves of deportees joined the previous generations of the Polish exiles. Many of them participated in armed struggle against Russia.

(…)

We thank prof. Marek Jan Chodakiewicz for sharing this article.