Poland’s de facto state of emergency under left-liberal rule

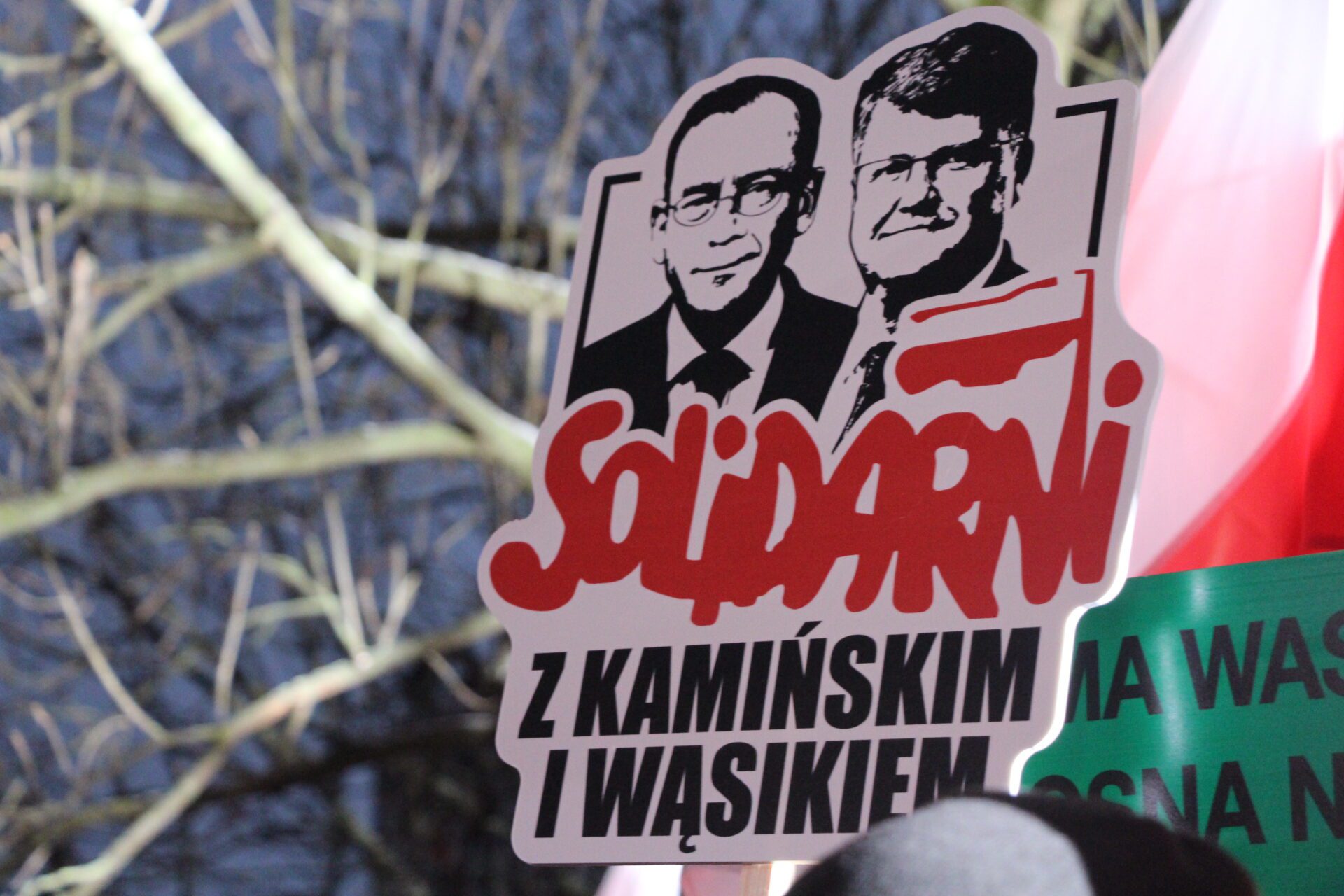

According to former social-democratic, post-communist President Aleksander Kwaśniewski, the detention and arrest of PiS Interior Minister Mariusz Kamiński and Deputy Minister Maciej Wąsik “is possibilism of the rule of law,” “possibilism” being a term coined by Kwaśniewski to describe a strong state that is capable of effecting change.

Paweł Lisicki

I cite this opinion because it shows that even those who were previously able to maintain a certain distance from the ongoing domestic political war in Poland, and who should be the first to respect the office of the head of state, have succumbed to emotions, joined in the brawl, and questioned the importance of the institution of president. There is no doubt that the source of the current conflict is the undermining of the meaning of the right of pardon – a right which, as is clear from the Constitution, is vested in the president. It is true that due to recent developments – the arrest and imprisonment of two Law and Justice (PiS) politicians, their undertaking of a hunger strike, and their wives’ requests for the president to do something – President Andrzej Duda eventually decided to pardon them again, but this did not change the essence of the dispute.

The argument [made by the judge who condemned the two men as well as by Donald Tusk’s government, which executed the court order despite it being a breach of several rulings by Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal] that the president can only exercise his right of pardon in a closed case where the verdict has become final is unacceptable for several reasons. First, such reasoning contradicts the interpretation that was given several times by the Constitutional Tribunal and by the Supreme Court’s Extraordinary Review Chamber. Secondly, such an interpretation that the president, in order to pardon someone, must wait for the final judgment of a court of last instance would in practice limit the president’s power in this regard.

The office of president is term-limited, whereas the course and length of a judicial process depends on the will of the judges. A court would simply need to drag out a case until a president’s term comes to an end to prevent the president from exercising his power of pardon. Making the president’s right of pardon conditional on a court ruling of last instance therefore leads to the politicization of the judiciary. Judges could conduct trials for longer or shorter periods depending on what kind of presidential reaction they expect. They could easily wait out a president they don’t like, especially when judicial proceedings involve politicians.

The right of pardon would thus become illusory, and that is exactly what happened in the cases of ministers Kamiński and Wąsik. In order to have them freed soon, President Duda has had to start new pardon proceedings, which calls his authority into question.

The crux of the dispute, however, is not a legal issue, but something else: the assumption made by the current ruling coalition that is led by Donald Tusk’s Civic Platform (PO), according to which it is in effect not bound by the laws and regulations that were passed under the Law and Justice (PiS) governments.

This position is not only absurd, but also detrimental to the interests of the Polish state. It wrongly implies that there is a bigger difference between the PiS-ruled state and the PO-ruled state than between the former communist Polish People’s Republic and the current Polish Third Republic. The current rulers behave as if they had come to power not through normal democratic elections, but through a coup and revolution.

It is as if they really believed what the craziest faction of the anti-PiS supporters say – namely, that there has been a victory over an authoritarian regime and similar things. It is as if the Polish state had lost its continuity during the era of PiS rule. It is also as if the previous PiS parliamentary majority had never legally existed, to an even greater degree than in the case of the People’s Republic!

This approach is contradictory. Indeed, if the Polish state was “corrupted and tainted” by the very fact of PiS rule, then consequently the new government should not have accepted to be sworn in at the Presidential Palace. Likewise, it should not respect Andrzej Duda’s constitutional right of veto, and simply pass laws in defiance of the presidential veto, which would thus be “suspended.”

Donald Tusk’s left-liberal authoritarian revolution: Poles are facing something completely new

Furthermore, Donald Tusk’s new left-liberal government should not take into account the rulings of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal – which, after all, is essentially illegitimate and illegal. How can this be reconciled with the fact that the current parliamentary majority formed a legitimate government through legitimate elections? How did the current legitimate government emerge from a state of legal nothingness – that is, from a state ruled by an authoritarian regime?

This defies logic. If PiS’ rule has so tainted the Polish state that there has been a break in legal continuity, then the current government is also illegitimate and has come to power not as a result of elections (since these, after all, could not be valid), but via a coup.

Thus, the parliamentary majority should be regarded as a truly revolutionary body that could only have retaken power on its own initiative and has thus had to rely on the use of force.

Everything that is impossible becomes possible if we resort not to law, but to violence. In practice, this means rule under a de facto state of emergency. This is indeed the “possibilism” which former President Kwaśniewski cheered about, because the government carries out its decisions. But this has nothing to do with the rule of law. On the contrary, it is governance by chaos and necessarily provokes growing public resistance.

The use of force and violence calls for violence in response. In order for the state to use “possibilism” without law, it must use more and more force, because this is the only way to ensure that its decisions are obeyed. We can easily predict where this will lead. This is a road to nowhere.

This article was first published in Polish as the editor-in-chief’s column in the Do Rzeczy weekly.