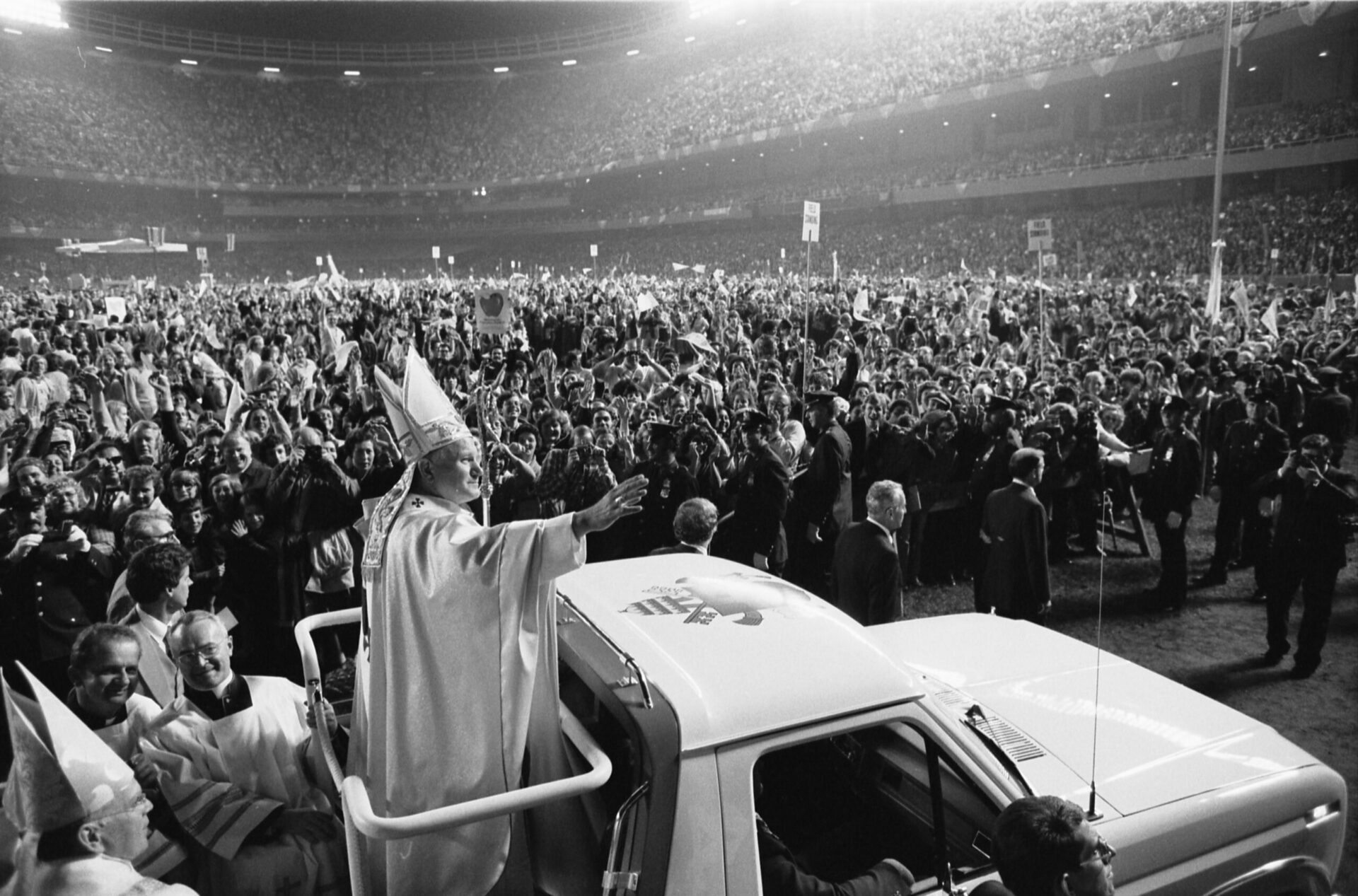

In defense of John Paul II

The Polish Pope has become the victim of an unprecedented smear campaign defaming his image. The facts clearly show, however, that John Paul II consistently fought against pedophilia and sexual abuse.

Tomasz Rowiński

The process of systematic vilification of John Paul II, which we have been witnessing for several years, can perhaps only be compared to how the opinion of Pope Pius XII was destroyed since the 1960s. Pope Pacelli died not only in the aura of sainthood, but also surrounded by universal respect. Israeli Foreign Minister Golda Meir wrote in a note of condolence sent to the Vatican in 1958, “Our times were enriched by this voice, vociferously articulating great moral truths, above the turmoil of the ongoing conflict. We mourn the great servant of peace.” Can no one make a parallel reflection about John Paul II?

Pius XII’s wartime attitude, saving many people through Church institutions, including Jews, was perceived as heroism in the post-war years. And this should not come as a surprise at all. The Pope himself expected that he might be arrested since he gave his associates a specific oral testament, from which it was implied that the moment of his capture should be treated as the moment of his abdication. The idea was that the German aggressors would not be able to blackmail the Church with the imprisoned Pope. Luckily, such a scenario never transpired. Unfortunately, however, a deftly organized plot by several intelligence agencies of the Communist bloc countries was enough to tarnish the opinion of Pius XII, to some extent irreparably. To this day, although the archives and the research of reliable historians deny it, one can still hear a painful insult thrown in the direction of this outstanding figure of the 20th century: “Hitler’s Pope”.

All that was needed to destroy the memory of Pius XII was false testimony crafted by the Soviet security services and the literary talent of playwright Rolf Hochhuth, whose play “The Governor. A Christian Tragedy” captured the popular imagination with remarkable success. Today, there is no need to resort to such subtle means as plays. Internet memes are enough, superficial publications suggesting preconceived theses, later multiplied by thousands of newspapers, magazines and Internet portals around the world. This is the modern problem with the memory of John Paul II that the Catholic Church has to contend with. John Paul II died, like Pius XII surrounded by universal respect, including from those who disagreed with his religious and moral teachings. He was the “Pope of human rights,” the “Pope who overthrew communism.” After a dozen years or so, all that remains in many circles is the slogan “The Pope who covered up Church pedophilia.”

One has to ask how this happened. The answer is simple. The basis for any disinformation to take root is the limited knowledge of the audience. Someone might doubt whether we can talk about disinformation in this case. But of course, John Paul II and his moral teaching, and more broadly the position of the Church, especially in the area of sexual ethics provoked and still provokes widespread resentment, sometimes even hatred. In such a state of mind, a person tends to seize every opportunity to subvert the authority associated with the object of resentment. Thus, it was enough for scandals within the circle of senior Catholic clergy associated with the Holy See to be exposed so that they could be linked to the figure of John Paul II. The easiest thing to omit from the coverage is the complex relationships that prevail in the Vatican dicasteries, among papal secretaries and officials, relationships that act in many cases like an information filter through which various factions and groups conduct their policies toward the Pope – any Pope. A look at this reality puts issues such as those we associate with the names of Cardinal McCarrick or Fr. Marcial Maciel Degollado in a completely different light.

In narratives about John Paul II, it is also quite easy to blur out the fact that the Pope heads a major institution – even if we consider only the Roman Curia and not the entire Church – he delegates various matters to his associates. John Paul II was increasingly aware in the following years of his pontificate that there were cases of sexual misconduct in the Church, and he wanted Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, to deal with this subject. Let’s remember that Ratzinger was Pope Wojtyla’s most trusted associate, and this means that John Paul II wanted the issue of sexual misconduct in the Church to be handled by someone who would perform his due diligence. He did not, for example, refer these issues to the Secretariat of State, where Cardinal Angelo Sodano, a figure of far less repute than Ratzinger, was in charge.

It may be worth adding at this point that in the late 1970s, at the start of John Paul II’s pontificate, when shortly thereafter first attempts were made to clarify Church legislation against sexual aggressors, the secular public debate in the West was still discussing the need to liberalize norms related to sexuality. In the 1970s, laypeople were allowed into the debate – inconceivable from today’s perspective – conducting deliberations on “good pedophilia.” Such was the climate in that era. Contrary to our perspective today, founded on a largely righteous moral disgust, for any institution, including the Church, sexual crimes were one of many issues that had to be dealt with. Sensitivity to the dangers posed by sexuality directed at minors was, unfortunately, much lower.

Finally, it is easy for the media coverage to ignore the legislative achievements of John Paul II’s pontificate. After all, who could have possibly comprehended these Church regulations! Reading the accusatory texts against John Paul II sometimes gives the impression that their authors expect John Paul II, like the Lord Jesus, to grab a whip and chase the bad people out of the Church. Reality shows, however, that even the most notorious cases of sexual crimes committed by predators in cassocks are far more complex than they might appear at first glance. Even if not at the level of facts, then at the level of perception. They require an examination of the credibility of circumstantial evidence or willing witnesses. The significant scale of false accusations against priests should prompt the Church to be prudent. The case of Cardinal George Pell is a clear enough example.

Crimen sollicitationis

So what did John Paul II do about the abuse of minors in the Church? Before answering this question, it should be added that the Church has promulgated canons against sins of a sexual nature at various synods over the centuries. The matter was also taken up by the 1917 Code of Canon Law, which threatened a priest who committed a sexual offense with a minor with various penalties, including removal from the clerical state. In 1922, the Holy See published the instruction “Crimen sollicitationis,” which gave a detailed procedure for dealing with situations in which a confessor makes sexual proposals to a penitent. This instruction was revised and supplemented in subsequent years.

The situation John Paul II found himself in at the beginning of his pontificate was not simple. There were still strong voices in the Church, saying that the Church in general – as part of the post-conciliar reform – should move away from disciplinary norms. Today, after a number of scandals involving Catholic leaders, we see how wrong this path was. The 1983 reform of the Code of Canon Law, which softened the penalties for church predators and the severity of the old canons, must be viewed from this perspective. However, given that these were years of leniency, the maintenance of disciplinary norms in these cases also represented a kind of success. It should also be noted that alarming signals about cases of clerical pedophilia began to flow to the Holy See only in the mid-1980s. This was probably due to the general loosening of customs in clerical circles, which had been taking place since at least the 1950s. At the same time, in the 1950s, ecclesiastical punishments fell on priests and religious causing scandal, and since the 1970s – unfortunately – all control was abandoned. We even had a kind of amnesia in the Church on these matters. This was the case, for example, with the Dominican Marie-Dominique Philippe, founder of the Community of St. John, who was also the “spiritual master” of Jean Vanier, founder of the L’Arche organization. Outlining these circumstances seems necessary to understand the situation in which John Paul II entered the papal office.

It is worth recalling how those years were summed up in 2019 by Benedict XVI, who, from the beginning of his collaboration with John Paul II, made many efforts to ensure that the Church did not ignore matters of sexual abuse:

“The issue of pedophilia only became pressing in the second half of the 1980s. It was already a public problem in the United States, so the bishops looked to Rome for help, because Church law as it was drafted in the new [Canon Law] Code did not provide for sufficient regulations to take necessary action. Rome and Roman canonists initially wrestled with the issue; in their view, a temporary suspension from priestly ministry must have been sufficient to effect a cleansing and clarification. The American bishops could not accept this.”

Since the 1980s, when awareness of the magnitude of the problem was still incomparable to today’s situation, more targeted changes began to take place. The apostolic constitution “Pastor Bonus,” reforming the Roman Curia, raised the profile of sexual cases and transferred them to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. What was missing from this constitution was a clarification of what acts were involved, if only by listing them. Nor was there an obligation on anyone to report cases of this nature to the dicastery. In 1989, the Holy See acceded to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, one of whose tasks was to prevent the sexual abuse of minors.

The topic of sexual crimes against minors also appeared in the new Catechism of the Catholic Church published in 1992. Article 2389 reads: “Similar to incest are sexual abuses committed by adults against children or young people entrusted to their care. This sin is both a bitter assault on the physical and moral integrity of the youth, who will bear its stigma throughout their lives, and a violation of educational responsibility.” John Paul II must have become increasingly aware of the disgraceful state of things prevailing in the United States in particular. At the same time, it seems, he still had confidence in the bishops of that country, which can be considered an important clue in Cardinal McCarrick’s case. This conclusion is based on simple data: contacts with the U.S. episcopate in the 1990s became more intense and mostly concerned the issue of sexual abuse of priests.

In 1993, John Paul II wrote a telling letter to the US bishops:

“In recent months I have become aware of how much you, the Shepherds of the Church in the United States, along with all the faithful, are suffering because of certain cases of scandal caused by clergy. On many occasions during the ad limina visits1, the conversations went in the direction of how much these sins of the clergy have shaken the moral sensibilities of many and create cause for others to sin. The Gospel word ‘woe’ has a special meaning, especially when Christ applies it to cases of depravity, and especially to the depravity of the ‘youngest’.”

The text shows John Paul II’s characteristic confidence in the community of bishops. Subsequent years showed that representatives of the higher clergy took advantage of this trust and misled the Pope on many scandalous matters. After all, it eventually turned out that the problem of pedophilia, or more broadly sexual crimes in the Church, is not a matter of isolated cases. On more than one occasion, it was the bishops themselves who created an institutional screen to shield the perpetrators, and even took part in sexual excesses and abuse of vulnerable people in various ways. In this context it is worth noting the change of addressees that took place between John Paul II’s 1993 letter and Benedict XVI’s 2010 letter. The second Pope no longer writes to the bishops, but to “Irish Catholics,: that is, in fact, to the victims and hurt laity, excluding the hierarchy.

Anti-testimony of the bishops

In 1994, John Paul II also issued an indult2 that brought Church law into line with U.S. law, such as raising the age of those treated as minors from sixteen to eighteen. The Pope hoped that his efforts would be enough of an impetus to change the situation in the Church in the United States. This did not happen, however, as many hierarchs were already showing no goodwill in matters of sexual misconduct, and a conspiracy of silence was becoming a way for some of them to react both in the face of accusations from the secular world and pressure from the Holy See. The said indult was also extended to Ireland in 1996. It was the anti-testimony of the country’s bishops that became one of the factors undermining the Holy See’s confidence in local episcopates. However, it took a few more years for this to happen.

When one reads John Paul II’s 1999 speech, delivered during the ad limina visit of the Irish bishops, one can see that John Paul II still clung to this trust. On the one hand, he appealed to his “brother bishops,” and on the other hand, he saw them as those who suffer from the iniquities of their subordinate clergy. “I am close to you in pain and prayer, entrusting to God all comfort for those who have been victims of sexual abuse by clergy or friars. We should also pray that those who have committed this evil will recognize the malicious nature of their acts and ask forgiveness,” – the Pope wrote. John Paul II was thinking of the victims, but as it seems it was still unthinkable to him that the problem was so deep. The case of Polish hierarch Archbishop Juliusz Paetz, Metropolitan of Poznan, showed how the Pope could be restricted when it came to access to information.

Was John Paul II’s attitude a sin of naiveté? That’s hard to say at a time when we know much more about the social mechanisms involved, not only in the Church, in sexual crimes and their cover-up. No doubt, however – often led by people with bad intentions – John Paul II made mistakes. However, there is no indication that he “covered up pedophiles.” Rather, he seems to have tried to act in proportion to the knowledge he had, and in proportion to the perception of the problem that was available to him in at the time and under those circumstances.

Things took a new turn after the publications of the Boston Globe, which left no illusions about the gravity of the crisis the Church was facing. It was 2002, the last three years of the Pope’s life were beginning. During a meeting with cardinals and the presidium of the US episcopate in April, a hint of doubt could be heard from John Paul II regarding the attitude of the bishops. “The great evils perpetrated by some priests and friars have caused people to now look at the Church with distrust, and many are outraged by the attitude they think the heads of the Church communities have taken toward this matter. Abuse, which is the cause of the current crisis, is in every way an evil and is rightly considered a crime by society; it is also a terrible sin in the eyes of God.” – John Paul II said. This “as it seems to them,” can be seen simultaneously as doubt as well as a desperate attempt to salvage trust in the Catholic bishops.

At the time, an apostolic letter Sacramentorum sanctitatis tutela on the protection of the sacraments was issued on the Pope’s own initiative (motu proprio), which contained norms for dealing with cases of grave crimes reserved for judgment by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. A set of norms of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith “De gravioribus delictis” (“On the gravest crimes”) was also issued. Both documents were a necessary correction to the new provisions of the 1983 Code of Canon Law. It can be said that they directly reinstated crimes of sexual nature against minors to the catalogue of the most serious offenses. Since the publication of these two documents, investigations of such cases were no longer under the authority of diocesan bishops, but were delegated to a Congregation headed by Cardinal Ratzinger, who devoted one day each week exclusively to these subjects. It was Benedict’s pontificate that bore much of the fruit of this preparatory legal work. In 2014, news agencies reported partial data according to which, in 2011-2012 alone, Pope Ratzinger removed nearly four hundred priests from the clerical state for pedophilia and sexual abuse.

In the above context, it is worth citing two specific and high-profile cases, the first of which cast a shadow over the person of John Paul II, as it showed that he was willing to put too much faith in the goodwill and discernment of his colleagues, while the second undoubtedly exemplifies the personal integrity of the Polish Pope, but also gives a picture of the systemic collusion that may have been at work in matters of a sexual nature.

In the late 1990s, the ecclesiastical career of former cardinal, and even ex-priest, Theodore McCarrick was gaining momentum. He then became a candidate for the Episcopal See in Washington, which traditionally entailed a cardinal appointment. McCarrick was garnering favorable reviews in the US episcopate at the time, and there was no indication that he would face any difficulties on his way to the ecclesiastical apex. There was, however, some significant criticism. The New York Metropolitan, Cardinal John O’Connor, after earlier discussions with other bishops, addressed a letter to the Apostolic Nuncio to the United States, dated October 28th, 1999. In it, he wrote that while he had no direct information, he considered McCarrick’s appointment to the new office to be a mistake that threatened scandal. At issue were increasingly widespread rumors that the archbishop had in the past shared a bed at his headquarters with young men, and also with clerics at his seaside home.

John Paul II, when the matter reached him, reacted without delay and instructed then-Nuncio to the US Archbishop Gabriel Montalvo to investigate the accusations. “The opinions collected in writing, again, gave no concrete proof: the information of three of the four New Jersey bishops consulted was described in the Report [this is the Vatican report on the McCarrick case – editor’s note] as “inaccurate and incomplete.” The Pope, who had also known McCarrick since 1976 because he had met him during one of his trips to the United States, agreed to the proposal expressed by […] Montalvo and then Prefect of the Congregation for Bishops Archbishop Giovanni Battista Re to withdraw McCarrick’s candidacy. It was felt that, despite the shortage of details, it was inappropriate to risk moving the hierarch to Washington so that the accusations, even if unfounded, could spread causing embarrassment and scandal. It seemed that McCarrick would remain in Newark.” This is how Andrea Tornielli, a journalist who today can hardly be regarded as an author sympathetic to the Pope in Poland, described the situation in his summary of the Vatican Report.

Then came the twist. McCarrick, when he learned of his situation, sent a letter to Bishop Dziwisz on August 6th, 2000, assuring him that he had “never had sexual relations with any person, male or female, young or old, clergyman or layman.” The letter found its way into the hands of John Paul II, who gave credence to the American hierarch’s passionate assurances, expressed in person during the meeting. He chose to ignore the accusations based only on hearsay. At the time, the theme of harassment of minors, or pedophilia or ephebophilia, was still not present in the case of McCarrick. Eventually McCarrick ended up in Washington, D.C., and while there he was given a cardinal’s hat. According to testimonies, John Paul II was guided by goodwill and experiences from the communist dictatorship in Poland, where it was normal for bishops and priests to be compromised on the basis of accusations believed to be false. John Paul II also trusted the majority positive opinion that McCarrick had in the United States. One would have to ask why this opinion was positive, when things were beginning to boil over in the American Church because of the future cardinal.

The second case worth mentioning is the scandal surrounding the person of Poznan Metropolitan Archbishop Juliusz Paetz and his removal from office in 2002. This case is noteworthy because in its various journalistic descriptions it is often emphasized that at a time when the archbishop felt threatened by the growing outrage over information that he was molesting seminarians, there was a phenomenon of isolating the now ailing John Paul II from people who could present the matter to him factually.

In the autumn of 2020, on the airwaves of RMF FM radio, Jaroslaw Gowin, editor-in-chief of the Znak monthly at the time, said about the situation between 1999-2002: “(…) at that time in our activities we often encountered a wall of resistance from the church institution. A key brick in this wall was the then secretary of St. John Paul II. Among those who were involved in the circumstances of clarifying the true, unfortunately, allegations against Archbishop Paetz, the awareness of the role of then Bishop Dziwisz, today Cardinal Dziwisz, was full.”

It should be emphasized that this is only one of the many testimonies that can be found in the Polish literature on the case of Archbishop Paetz. Besides, the problem of “blockade” concerned a much wider range of Polish hierarchs, as Polish journalists, including those connected with the Church, have written about in detail several times. The matter was brought to a conclusion only thanks to the “secret” mission of Wanda Półtawska. Being a personal friend of the Pope, she had direct access to him and no one could stand in the way of her meeting with John Paul II. She handed him a letter hidden under her blouse describing the situation.

“None of us cared about publicity. It was solely about the welfare of the clerics. We wanted to avoid unnecessary scandals, and when official avenues failed, it was necessary to use the intermediary of someone in whom the Pope had boundless trust. I never spoke to Dr. Półtawska about it, but I am told that she brought the letter to dinner hidden under her blouse. I’m convinced that if it hadn’t been for her intervention, the whole thing would have taken much, much longer.” – Fr. Tadeusz Karkosz told Tomasz Krzyżak, a journalist for Rzeczpospolita in 2015. Archbishop Paetz eventually left, taking revenge along the way on those he considered guilty of his downfall.

A similar obstruction may have occurred in the case of Fr. Maciel Degollado – founder of the Legionaries of Christ. In the pages of the Catholic weekly Gość Niedzielny, Paulina Guzik, a journalist known in Poland for exposing and describing several cases of serious clerical sexual abuse, said, “As far as I know, the only reliable journalistic investigation of the case was carried out by (…) Valentina Alazraki, who for a decade covered the issue of the serial offender, manipulator and fraudster – Fr. Maciel. Today she says with full conviction that the Pope did not know about it.” In that interview Guzik also pointed out that the media and the public too often operate on the principle “because we think – that ‘the Pope must have known.’” Establishing the truth usually requires considerable effort.

How many cases like that occurred at the time? How many of them reached John Paul II only in the form of rumors or unverified gossip? How many of them may have been presented in a distorted manner by close associates who wanted to lower their gravity? This we do not know. What we do know is that John Paul II, with the help of Cardinal Ratzinger, sought to change the Church system. This was the only way out; it’s hard to imagine the Pope devoting all his energy to specific cases of iniquity when there are hundreds of them at various levels of the Church hierarchy. However, it is apparent that when someone reached out to John Paul II personally he was able to achieve the desired effect – in the case of Cardinal McCarrick, a notorious liar – tragic – in the case of Wanda Półtawska – positive. Perhaps this was the biggest problem with and of John Paul II. He trusted people a lot. Sometimes too much.

1 the required visit of Catholic residential diocesan bishops and certain prelates with territorial jurisdiction to the tombs of the Apostles Peter and Paul as well as to meet the Pope to report on the state of their dioceses or prelatures.

2 Under Canon Law, an indult consists of granting a permission or privilege by the Holy See or the diocesan bishop, as the case may be, for an individual exception from a particular norm of Church law.