Five graves in the Ural Mountains. The tragedy of the Polish family in the USSR (Part 2)

An interview with prof. Stanisław Kulon, an exile and artist bringing to light the tragedy of Siberians

(…)

Let’s talk about the Russians who, even under those conditions, did not lose their humanity. Have you met many such people on your way?

There weren’t many of them, but I still remember each person like that. After arriving in the city of Molotov (today it’s Perm), we were taken in trucks for a two day journey. Then an old peasant took us in a sleigh to the place of exile. On the way, we stopped for the night at his house and were received very warmly. We were finally able to eat after more than a month of train travel in terrible conditions. I noticed that in the corner of the house was a portrait of a bald man with a beard. After dinner, we went to sleep. Our hosts cleaned up after dinner and made sure we were asleep. Suddenly, with curiosity, I saw an icon light up in the corner, and they crossed each other three times and began to pray. In the morning a bald man with a beard stood in the corner again…

Those who feed the hungry are somehow especially remembered. After my mother died, we became orphans. That was before we were put in the orphanage house. We even thought about how to commit suicide so that it wouldn’t hurt us. I had to beg for food with my sister. People mostly chased me away, at most I got a potato or a piece of bread. One day, however, an indescribable happiness befell me: an old lady gave me an egg. Can you imagine what an egg was like to us back then? I told this woman that for that I will be grateful to her for the rest of my life.

How did the Soviet Union treat orphans in the houses?

First memory: Other children attacked us and took the bread that we got as our first meal. We were not used to such behavior. From then, we knew that you had to hold your piece of bread tight. Hunger was commonplace there. I had to sneak into the kitchen, where I picked the biggest peels from the garbage can and toasted them in the oven. It was considered a rarity.

In the afternoon, the dogs always waited by the canteen, where the cooks dumped the leftovers after dinner. We also waited there. We would then fight for the food with the dogs. However, we had an advantage over them because we had sticks. It was all the horridness of the Soviet system in a nutshell. We were told that we were extremely lucky because we lived in the Soviet Union under the protection of Stalin. Meanwhile, in this Soviet “paradise” we were fighting for food with dogs…

Only once a year we got a few candies and biscuits “from Stalin”.

As I understand it, you did not believe all this propaganda even for a moment?

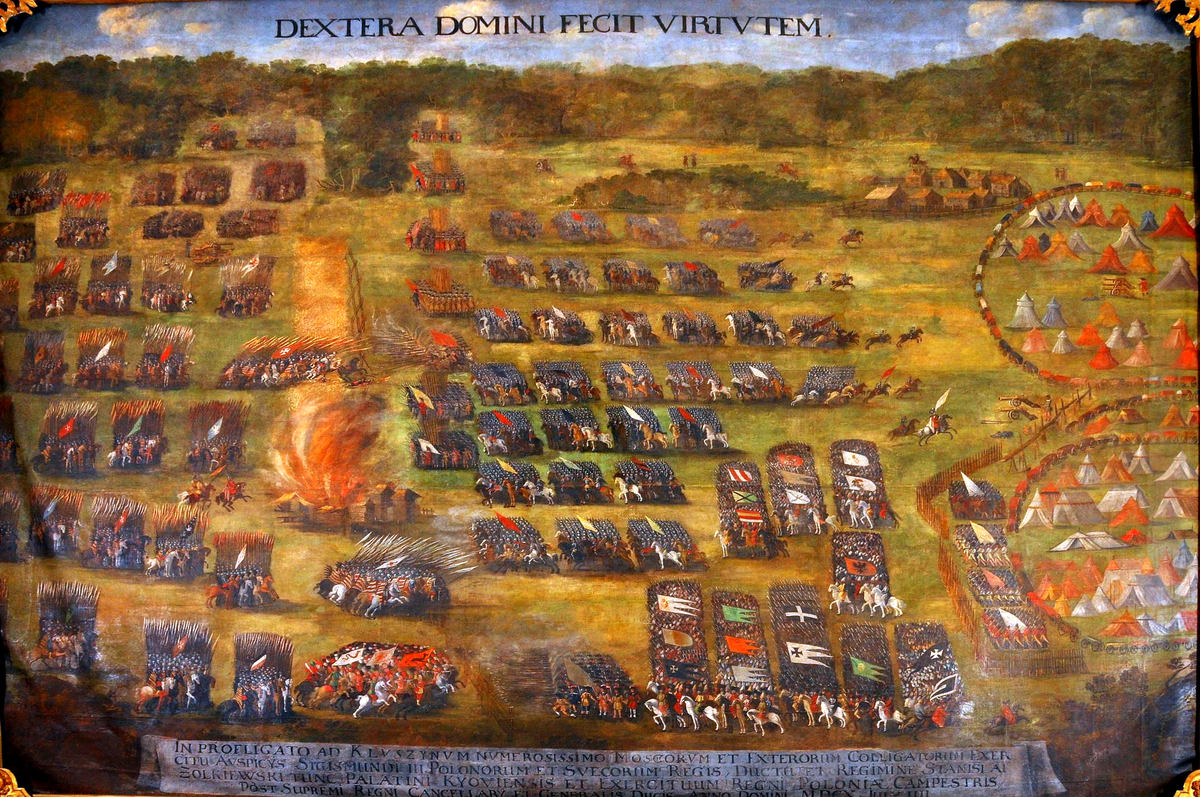

No sir, the son of a Polish legionnaire, a participant in the Warsaw Battle, was naturally resistant to such nonsense. In exile, my father claimed – probably rightly – that all this was Stalin’s revenge for Poland’s victory at the Battle of Warsaw in 1920.

How did you discover your sculptural talent?

It was in an orphanage house in Rostov-on-Don at the turn of 1944/45. The city was hugely damaged, we were planning to rebuild the house. We were rubbing blocks of chalk on plastering dust. One day, out of boredom, I started sculpting chalk into the shape of…my shoe. The manager caught me. He yelled at me, confiscated my chalk shoe and called me a saboteur! I thought I was going to have big problems. After two days, he came to me and … asked me to make a second shoe, because his wife liked it a lot (laughs). This is how my sculptural passion began.

Despite being 87 years-old, you are stilling active, creating new works about the exile. Aren’t you dreaming of a long-deserved rest?

I am the last living member of the Kulon family to survive a deportation. Telling the story of that world is something I consider my sacred duty to the relatives lying in the Ural land.

The interview was conducted in 2017.

* Prof. Stanisław Kulon (1930-2022) was a sculptor and lecturer at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw for many years. In 1940, he was exiled by the Soviets from Poland to the Soviet Union.