The eternal struggles with Moscow and their reflection in art (Part 2)

The struggles of the nations of Central and Eastern Europe with Moscow have been going on for over 500 years. Poles, Lithuanians, Ruthenians, and Ukrainians (Cossacks) stood together to defend their freedom. They are represented in many fascinating works of art that are still awaiting permanent entry into the national imaginarium.

Jerzy Miziołek

(…)

Kluszyn (1610) and Smolensk (1611)

A figure who combines the war triumphs of Batory’s time with those of Sigismund III is Jan III’s grandfather – Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski. The titles to his glory – and the triumphal march in Warsaw in 1611 – were not only the brilliant victory at Klushyn and the conquest of Moscow, but also the well-known prudence and wisdom that King Sigismund III did not always want to utilise. Hetman’s wisdom and virtus bellica are attested to by his writings: “The Beginning and Progress of the Muscovite War” of 1612 and “Encouragement to Virtue [of War]” from 1618, where, on the basis of one of the battles, when he had to rely on to the overwhelming enemy forces (as then at Cecora), he invokes Thermopylae and the struggles of the Greeks with the Persians, whose place in his narrative is taken by Poles and Turks.

Zygmunt III, the signing of the treaty with Sweden in Vyborg against the Commonwealth by Tsar Vasyl Shujski (in February 1609), prompted the military actions against Moscow. The king’s main goal was to regain Smolensk. On September 21st, Polish-Lithuanian forces crossed the Moscow border, and Lithuanians with Chancellor Lew Sapieha stood outside the walls of Smolensk on September 29th. Zygmunt III himself, at the head of the Polish troops, reached Smolensk on October 1st, and thus a siege began. Its success would not have been possible without the victory at Kluszyn.

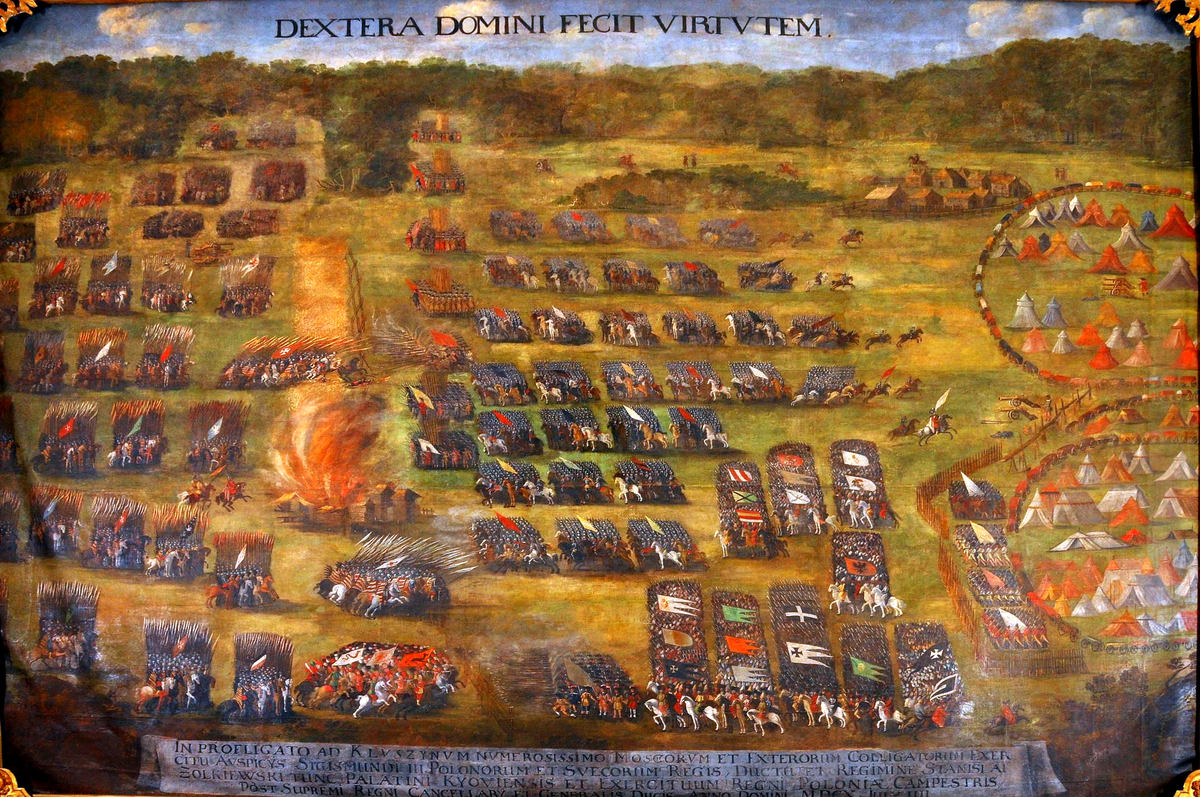

In June 1610, the Moscow army, commanded by the tsar’s brother, Dmitri Szujski, set out to help the besieged fortress, supported by a corps composed of foreign forces, mainly Swedish. The army numbered over 30,000 men. The troops sent against them, commanded by Hetman Żółkiewski, supported by the Cossacks, were more than four times smaller. On July 4th, there was a clash in the fields of Krušinsky, where, as a result of many cavalry charges, the Moscow forces were completely destroyed and forced to flee, and the foreign corps capitulated, seeing the pogrom of the tsarist troops. In a letter from the hetman to the king of July 5th, we read: “After so many turns, theirs and ours, the bravery of Your Majesty’s knights overwhelmed the enemy, first Moscow and then the foreigners began to flee. Your Majesty’s soldiers rode into their camps on horseback, hitting and cutting them so that they and their camp were driven into the forest”.

A priceless supplement to written sources is a large painting (600 x 600 cm) by Szymon Boguszowicz, which Żółkiewski commissioned for the church in Żółkiew (currently it is located in one of the churches near Lviv). In its center, we see two banners of the Polish hussars attacking the enemy cavalry. The image, which also shows the queen himself on horseback, indicating the direction of the attack with his mace, is an important source of knowledge about military tactics (arranging troops in a checkerboard pattern) and weapons. A small Polish-Lithuanian-Cossack army stopped the pressure of the Muscovite troops, opening the way to Moscow and making it possible to capture Smolensk.

Smolensk was stormed on June 13th, 1611 as a result of an explosion of a firecracker planted by Bartłomiej Nowodworski under one of the towers. Many buildings burned down as a result of the explosion of gunpowder supplies; Several thousand townspeople and several hundred soldiers of the crew were killed. After 97 years of Moscow rule, Smolensk was returning to the borders of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Sigismund III, in memory of Victoria Smolensk, ordered a gold medallion with the inscription: “Smolenscum captum die 13 junii 1611”. The tribute of the Szujski tsars before Zygmunt III and his son Władysław took place on October 29th in the Senate Hall at the Royal Castle in Warsaw. It was an expression of the power of the Republic of Poland and emphasized its advantage over Moscow, which was accentuated by Hetman Żółkiewski in his speech.

The conquest of Smolensk is commemorated by a large drawing described as “Equestrian portrait of Sigismund III against the background of Smolensk”. It is a repetition of the composition of the painting by Tomasz Dolabella, as mentioned in the inscription on the drawing. The figure shows the victorious monarch as a rider with a huge mace in his right hand, dominating the image of the captured city of the fortress visible in the upper left corner of the composition. The rider tramples the defeated enemy, while the triumphal procession arrives from the left. The six riders are escorting a group of footmen – prisons, appearing dignified and dressed in long robes – followed by two trumpeters announcing victory.

King Władysław managed to defend Smolensk from another attack of Moscow in the years 1634-1635, but the pressure continued. The loss of the fortress took place in 1654. The Commonwealth did not regain it. In January 1667, this painful loss of the city, which opened the road to Vilnius and Warsaw, was confirmed by the Treaty of Andrus. Finally, the “Eternal Peace” signed in 1686 with Moscow gave her the Smolensk district along with Smolensk itself.

Earlier, in the fall of 1660, the last military triumph of the first Polish Republic over Moscow took place; it was the Battle of Cudnowo, in which the Polish-Lithuanian army was commanded by two hetmans – Stanisław Potocki and Jerzy Lubomirski. On June 17th, 1661, “The Polish Mercury”, a newspaper at the time reported: “No pomp and magnification have more eye-catching as a solemn cavalcade of hetmans leading prisonerss and Moscow signs through Krakowskie Przedmieście to the Castle. In the Senatorial Chamber, where the Russian leaders were presented to the king [Jan Kazimierz] […], the victorious insignia threw the soldiers in front of His Majesty’s legs at the canopy”.

260 years have passed since the victorious battle of Cudnów to the Miracle on the Vistula in August 1920. At that time, despite Piłsudski’s great efforts, it was not possible to federate the Second Polish Republic with Ukraine. A significant part of it then fell into the Moscow abyss, from which now – to the amazement of the whole world – it heroically rises to freedom.

This article was published in August 2022 in “Do Rzeczy” magazine.