The Intermarium Now: Strategy and Tactics

The Intermarium is back in good graces as a conduit of American (and other) assistance to fight the war in Ukraine

Prof. Marek Jan Chodakiewicz

Vladimir Putin has recently opined on alleged Polish plans regarding the war in Ukraine. It is to restore Poland’s empire, the Intermarium. The Intermarium, or lands between the Baltic, Black, and Adriatic Seas, emerged first as a viable geopolitical concept under the Jagiellonian dynasty, Grand Dukes of Lithuania who became the kings of Poland, in the 15th and 16th centuries. The area receded into obscurity along with the decline of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 18th century. It briefly returned to local prominence in the wake of the First World War and the dissolution of the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and Prussian/German Empires. It was soon crushed by the Third Reich and the Soviet Union.

However, the Intermarium, as cooperative or even a federative entity, once again reemerged in theory and practice after 1989. What can be done to make it a success? There must be regional solidarity. Toward that end, there should be a comprehensive integration of all interested parties, including at the grassroots level. Some of these processes have already commenced because of, and despite of, the war in Ukraine. Let’s look briefly then at the past, present, and future.

The heirs of the Commonwealth

The concept of the Intermarium itself harkens back to the Jagiellonian dynasty of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland in the 15th century. Within the next hundred or so years the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita) carried forth the idea. The assumption was that the Commonwealth with its numerous nobility of many ethnicities (its political nation) would continue to play an important role pushing both Muscovy and the Ottoman Empire out of the region, while promoting unity of the local peoples as taught by the Latin civilization of Western Christendom.

With the collapse and disappearance of the Commonwealth at the end of the 18th century, the project receded as the Intermarium fell into the hands of four empires: the Romanov, the Hohenzollern, the Habsburg, and the Ottoman, even if the last named had withrew from Europe almost completely by 1914.

Meanwhile, however, as the heirs of the Commonwealth continued to dream of freedom they would invoke in their struggles not only the Res Publica Serenissima, but also its broader framework of the Intermarium. To a large extent, the Romantic slogan “For Your Freedom and ours” reflected this sentiment.

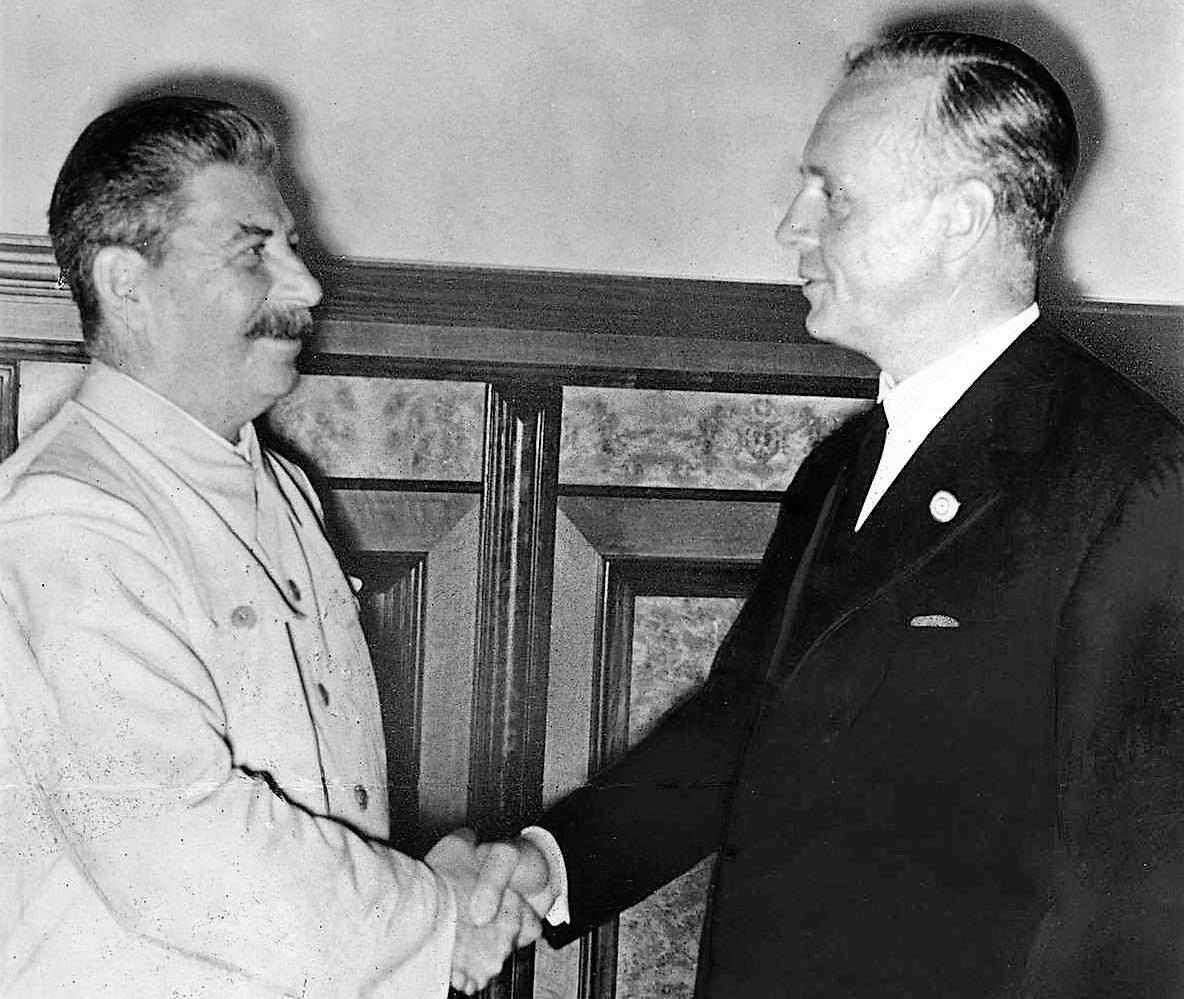

When the four empires ultimately collapsed in 1918, Poland, once again, took the lead to resurrect the idea of the Intermarium, as an “in-between” block between the revisionist powers: Germany and Soviet Russia. Sponsored by Warsaw, the Promethean Movement, uniting all anti-Bolshevik non-Russian nationalists, was one manifestation of the spirit of the Intermarium. After 1939 there was even a plan of a Polish-Czechoslovak Federation.

However, the outcome of the Second World War put paid to the dream once again. The Soviet Union totally occupied and controlled the Intermarium. Some nations experienced direct occupation, while others an occupation by proxy with native Communists doing Moscow’s biddings. One of the most important objectives was to deny the region sovereignty and possibility to cooperate together.

Region combinations

After 1989, as the lands between Baltic, Black, and Adriatic seas regained their freedom, some have once again circled back to the idea of regional unity and cooperation. On their own, the denizens set up the Visegrad Triangle, later Quadrangle, and, finally, Group (Poland, Czechia, Hungary, and Slovakia) – and other such region combinations. Overwhelmed as they were by the vision of the European Union, they lacked their own vision and resources, though the heart was in a right place.

Naturally, Brussels and Berlin have long looked askance at alternative ideas and structures, such as the Intermarium, that may be perceived as competition to the EU. No help was therefore forthcoming to foster the revival of the region on its own terms.

The United States deferred to the UE understood as primarily “Western Europe”. Until recently, Washington largely ignored the post-Soviet zone, including the Intermarium. The exception was NATO and the services rendered by most of the nations there to the US-led “War on Terror.” The Intermarium became the “New Europe” in the parlance of American diplomacy, albeit rather briefly.

This rhetorical device served more to stick it to the Western Europeans, the French and Germans in particular, rather than to pursue a constructive, long-term policy toward the lands between Baltic, Black, and Adriatic seas. America continued to perceive the region primarily through the prism of Brussels, Berlin, and Moscow.

That changed to an extent in 2016. The concept of the Intermarium started gaining traction at the White House. There were two main priorities.

First, strengthening NATO’s eastern flank militarily against Russia’s anticipated aggression would allow the United States to move its resources to, and focus on, the Pacific to counter China.

Second, investing in the Intermarium’s infrastructure to create an energy hub in Poland, Croatia, and Bulgaria to be supplied with American gas and oil would be the best way to provide energy security for the European Union and its neighbors. It was a win-win situation for everyone. The Americans would make money, and the Europeans would ditch their energy dependency on Russia.

Unfortunately, after the election of 2020, the new American leadership abandoned the plan. Washington attempted to placate Germany and to cozy up to Moscow. However, following the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the narrative changed again.

The Intermarium is back in good graces as a conduit of American (and other) assistance to fight the war in Ukraine. This entails certain American investments but mostly in military related issues. That is not enough for the region and it is obvious that the White House lacks any long term strategy there.

Investment commitments

The governments of central and eastern Europe should concentrate on taking advantage of the situation to translate this fleeting military interest into more permanent American security and investment commitments.

All nation states in the region should endeavor to conclude as many bilateral deals with the United States as possible. They should go beyond military matters and concern trade, infrastructure, and other projects.

Further, these nations should coordinate amongst themselves to act as a block to encourage the US to get used to dealing with them as a united entity of the Intermarium with interests in common. There is no need at the moment to involve everyone in the region, but eventually it may be very efficacious to do so. For example, the Baltic states can act alone vis-à-vis the White House in matters concerning themselves only. However, if the matter is more universal, pertaining more than them alone, they should approach the Visegrad Group to join them for added weight.

Of course it will be necessary to learn how to work toward the goal of the Intermarium solidarity in a variety of combinations. For example, a united block of NATO’s Eastern flank states will get more traction not only within the Alliance itself but also dealing directly with America. Similarly, the eastern flank’s EU members should coordinate their negotiations with DC and, if needs be, they should speak up on behalf of non-EU participants, say Northern Macedonia or Moldova.

Incidentally, this approach could apply to any situation that pertains to the conduct of foreign policy. For example, Czechia has been outspoken against human rights violations in Cuba. Prague can handle Havana alone, but should it require assistance, it should enlist other Intermarium allies for the cause.

Another example: Lithuania has been at the loggerheads with China. Now, after a while, the other Baltic states have joined Vilnius in defying Bejing. If it is in the interest of the Intermarium, other nation states should line up with the Balts in this endeavor.

There are some encouraging signs that solidarity has been emerging in the Intermarium. For example, in Brussels, the central and eastern European states have stubbornly insisted to bring to account Communist mass murder and other crimes. That does not sit well with many Western European leftists and other Marxist apologists, but so far the Intermarium block has held firm at the European Parliament.

Another sign of solidarity is that the same block tends to be America-friendly in the EU. One must therefore bemoan Brexit only on this account: Great Britain acted the same way as the Intermarium nations. Now, the British are gone and the Poles and others from the Intermarium are not enough to offset the Franco-German team’s current anti-Atlanticism.

However, the Brits are still in NATO. There should be as close cooperation within the Alliance as possible. Troops should rotate for military and cultural training. A month in Estonia by a Spanish soldier may help him grasp the danger of Russian imperialism. A stint in Portugal by a Czech border guard will amply demonstrate the threat on uncontrolled immigration from the Third World.

Three aspects

All in all, the Intermarium governments have their work cut out for themselves. And the common people? They should not allow their elected leaders to steal the show. It is not enough to vote for Intermarium-friendly politicians. The people should continue to be active, and expand their activities, on several levels.

First, local governments at the village and town level should reach out to their analogous counterparts in each of the Intermarium nations and create (or strengthen) a network of sister cities and sister hamlets.

Second, local chambers of commerce, businesses, and enterprises should follow suit. This should include gigantic state owned (or private – which is much less frequent in the region) conglomerates as well as tiny firms and everything in between. This is good for business and good for human contacts.

Third, there should be people to people diplomacy outside of government and business. For example, Croat teachers should travel to Latvia to compare notes. Hungarian kids should participate in high school soccer tournaments in Bulgaria. There should be locally endowed scholarships to study anywhere in the Intermarium one wants to.

Pretty soon, such grass roots endeavors can move from local and unilateral to regional and multilateral activities. Yet, the special relationships, forged at the bottom among and between the peoples of the Intermarium will endure and thrive. The bottom up ingredient is a crucial factor to foster regional solidarity.

Marek Jan Chodakiewicz

Washington, DC, 10 June 2023