The Autumn of the Patriarch: why did Tusk return?

Why is Donald Tusk obsessed with the opposition’s joint electoral list? To understand this, we must ask ourselves another question: Why did he return to Polish politics?

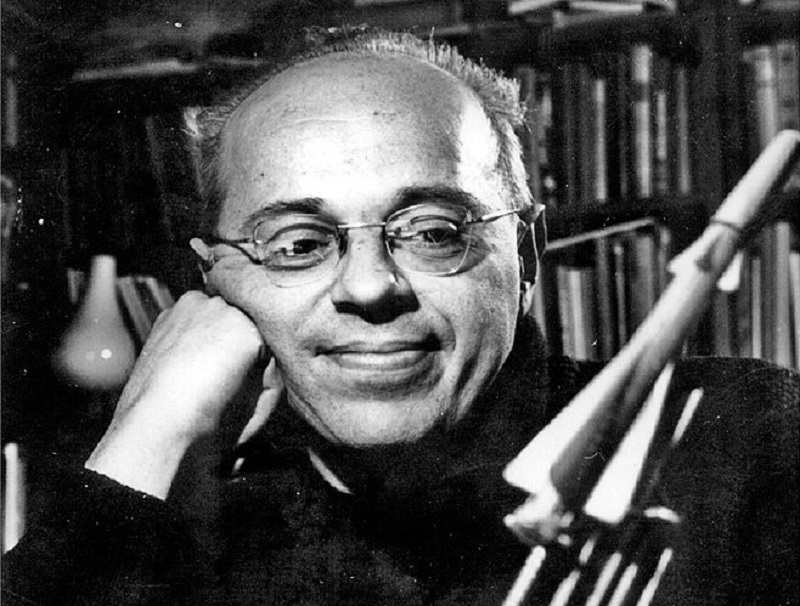

Piotr Gociek

Let us answer then: he returned to Poland because he had no other choice. If there was only a chance, a shadow of a chance, that he would continue his career outside the country, in EU or UN bodies, he would have certainly done so. During the second term of the Civic Platform government, Tusk repeatedly made his associates understand that Polish politics were already tormenting him and that he considered himself destined for higher things. The acolytes gazing into the king’s eyes found this to be natural and accepted his declarations with delight. Let us remember the words of Jacek Krawiec, president of Orlen during the term of the Civic Platform’s rule. It was he who said in an interview with Paweł Gras (we know these words from the tapes recorded in the Sowa and Friends restaurant): “But you’re going in a completely different direction, you’re separating yourself from all this, from this “fu***** crap, you’re a big bear, you’re distinct from this folklore, from this crap”.

In 2014, Tusk became a “big bear” when he assumed the position of the president of the European Council. One can laugh at the fact that, firstly, not as big as he thought (nice title with negligible meaning and potential), and secondly, that the big teddy bear was only a useful stuffed animal by German Chancellor Angela Merkel. This does not change the fact that Tusk took a step beyond Polish politics and had a prospect of making more. The fact that he failed was largely due to himself. Of course, Angela Merkel’s role as the driving force in the whole process cannot be overestimated – if she wanted to push for his candidacy for some other position later, she would have pushed it through – but Tusk did not meet EU standards in the slightest.

AN ISOLATED BEAR

Already in the summer of 2015, Paweł Sienniki noted in the Polska Times newspaper: “For the first year, the head of the European Council had a big problem with settling in the new position. He had to improve his English, he was accused of being passive and indifferent. He had to learn about European politics, which is based to the greatest extent on negotiations, behind-the-scenes agreeing on positions. Donald Tusk has not participated in such sophisticated games so far”. Polish media correspondents in Brussels told (and sometimes wrote) about how strongly separated from the life of the EU are Tusk’s colleagues and himself. They kept to the side, in their own circle, could not take part in the game for which they turned out to be completely unprepared.

Tusk himself was not eager to work hard, and when he tried to come out with his own message, it turned out that he lacked intuition. “I’ve been wondering what this special place in Hell looks like for those who promoted Brexit”, he fired in 2019, which secured him a spot on the news broadcasts but did not fit in with the acceptable rhetoric of the discussion at the time. When he tried to utter something about Russia (after 2014 he happened to say that Russia was a problem and suggested sanctions after the Crimea had been annexed), he was way off the mark, the EU elites were shuffling their feet to do business with Moscow as usual. He tried to balance himself on the refugee crisis. When in December 2015 he said in an interview with the “Süddeutsche Zeitung” that the borders of the Union should be better protected and that the wave of refugees was “too big not to stop it”, and opposed the forced relocation of immigrants from Turkey, he was told that He is overly guided by Poland’s internal interests and that “he is supposed to unite everyone, not polarize” (this was said, among others, by Rebecca Harms, chairman of the Green faction in the European Parliament at the time).

All this meant that, although in the spring of 2017 Tusk had no problems with extending the term of office of the president of the European Council for another two and a half years (Brussels and Berlin wanted to hurt the PiS government), after the end of his term, no one had anything else to offer him. After the end of Merkel’s era, he had no more friends. And he did not flicker with his own diligence and talent in Europe. The former prime minister, unlike Jan Krzysztof Bielecki, Jacek Rostowski or Tadeusz Kościński, who later served in the PiS government, did not have any qualifications to pursue a career in a large foreign bank or an international financial institution. For some reason these institutions are not interested in hiring those who specialize in the history of Gdańsk and in the mocking of Kaczyński.

TUSK’S LAST RESORT

Donald Tusk had no choice but to return to the only forest on the continent where he could still pass for a big bear – to Poland. But in what role? This is where the trouble began. The style in which he joined the campaign before the elections to the European Parliament (Spring 2019) did more harm than good. In the fall, PiS won the elections again and the Civic Platform, instead of dividing the spoils, had to deal with organizing life in the opposition again. A year later, the Civic Platform candidate for president was Rafał Trzaskowski (and earlier it was supposed to be, Małgorzata Kidawa-Błońska). It took Tusk some time to take control of the party and return to the position of its leader. He had no serious competitors in the Civic Platform. But things looked differently outside the party.

Rafał Trzaskowski, although still unable to properly manage the support and publicity he gained during the lost presidential campaign, is much better received by both the electorate and members of the Civic Platform. Włodzimierz Czarzasty is rebuilding the left. Szymon Hołownia and his “Poland 2050” took the place of “Nowoczesna” from the discredited Ryszard Petru, that is “the liberal party of second choice, which is not the Civic Platform”. PSL, containing the biggest zombies of Polish politics, is constantly laid to the grave and is constantly alive, no matter how grotesque its life is (that is: how grotesque are the successive “Polish coalitions” – most recently with Gowin and Piskorski). A scenario in which all these parties together were to defeat PiS, but starting from their own lists, is disastrous for Donald Tusk. In this quadrilateral (who knows whether it will not a pentagon – if a few swords are missing, PiS will have to strive for the support of Konfederacja). Negotiations will begin. None of the leaders of smaller parties will welcome Tusk as prime minister with open arms. A complicated game with everyone playing against him will ensue – and it will be a rational response. Because everyone remembers that Tusk is as ruthless and toxic towards his allies as towards his competitors inside the party. Donald Tusk will not be the name of the compromise candidate.

The start of one big list of the opposition, with Tusk as the leader and the face of “the return to normal”, is the only chance for the former prime minister to become prime minister again. And this is probably the only position he sees for himself in the near future. Therefore, he fights with a plea, a sense of danger and aggression for such a united list (Hołownia spoke about the “aggressive advances of the Platform” for a reason). Not only because he is still driven by pride and ambition. Not only because he is not smiling at political retirement. Not only because he wants vengeance against Jarosław Kaczyński.

FIGHTING FOR THE PAST

Donald Tusk is fighting today not for the future of the Civic Platform, but for his own past – to save his own past, that is, his achievements in the period from 2007–2014. With each successive year of PiS rule, with each subsequent crisis from which Kaczyński’s party emerges victorious, the splendor of Tusk’s past achievements fades. That he was the first to win two consecutive parliamentary elections and ruled two terms? PiS did as well. And it is closer to the third term than the Civic Platform was in 2015. He effectively appointed the candidate for President of the Republic of Poland (Bronisław Komorowski)? Well, Jarosław Kaczyński appointed three (Lech Wałęsa, Lech Kaczyński, and Andrzej Duda) and is on the way to the fourth. Successes in economic and social policy? A mere farce, the slogan of Tusk’s team was “there is no money and there will be no money”1. The symbol of the Civic Platform’s foreign policy will always be the Smolensk tragedy, a walk with Putin to the pier in Sopot and a foolish bet on Berlin to protect our interests.

Donald Tusk can reverse these trends, only by returning to the prime minister’s chair, once again becoming a symbol of the triumph of anti-PiS Poland and building the conviction that eight years of PiS rule was a glitch in the matrix. If there is no such triumphant return, then with each successive year Tusk will become more and more of an afterthought in the contemporary history of Poland, rather than its great hero. Only the victory of the united list of the opposition led by Tusk gives him a chance. Perhaps a shadow of a chance. But he will stick to it because he has nothing else to resort to. He is fighting to see the autumn of the patriarch in his political career, and not the autumn of the great failure. But others, instead of fighting for Tusk’s past, prefer to fight for their own future. Can anyone blame them?

This article was published in June 2022 in “Do Rzeczy” magazine.