Poland’s duty – finding the victims of totalitarianism

“Ceremonial funerals of a state nature, with military ceremonies, are the final stage of our work. Funerals that should have taken place years ago, but which never did. This is how Poland fulfills its duty to its citizens murdered in the 20th century” – says prof. Krzysztof Szwagrzyk, Director of the Office of Search and Identification of the Institute of National Remembrance and its Deputy President.

I would like to start by returning to the event and the words that have come to symbolize the subject of our conversation, that is, the effort that the Polish state puts into searching for the remains of its citizens murdered by criminals of various totalitarianisms. “The funeral of Danuta Siedzikówna ‘Inka’ and Feliks Selmanowicz ‘Zagończyk’ restores dignity not to them, because they never lost it, but to the Polish state, which for years, even after 1989, failed to honor its heroes,” said President Andrzej Duda during the funeral ceremony of the two victims of communism, whose remains were found by the team of the Institute of National Remembrance (INR) led by you.

I fully agree with these words, because said words uttered by the President during the funeral of Danuta Siedzikówna “Inka” and Feliks Selmanowicz “Zagończyk” in 2016 fully reflect the situation when the Polish state, through search, identification, research, and burial, carries out its duty and does so in a very tangible way. It is true that it is not the victims who have lost their dignity, it is the Polish state, by undertaking this duty – late, but nevertheless – that is regaining its dignity. It shows that it cares about Poles, about those who gave their lives, who died, who were murdered in the 20th century. These are extremely important, pertinent, very often quoted words in the public space, which perhaps accentuate this change like no other.

In Poland, the figures of “Inka” and “Zagonczyk” are well known, but foreign readers may be hearing about them for the first time. Let us therefore briefly introduce them.

At the outset, it is worth noting that the funeral of “Inka” and “Zagonczyk” in Gdansk in 2016 brought together more than 50,000 mourners, who took part in escorting them to their place of eternal rest. Danuta Siedzikówna and Feliks Selmanowicz were members of one of the units of the anti-communist underground commanded by Zygmunt Szendzielarz “Łupaszka.” The unit began its activities in 1943 in the Vilnius region, and ended its combat trail in 1948, although its remnants were still fighting battles in the early 1950s. In August 1946, the two partisans were executed in a prison on Kurkowa Street in Gdansk. Danuta Siedzikówna “Inka” had not yet turned 18 at the time of her death. Next to her was the body of her older, 42-year-old colleague from the underground organization.

These were two of a very large number of death sentences carried out by the communist system in Poland on soldiers of the anti-communist underground, which existed in Poland from 1944 until almost the mid-1950s and which took up arms against the Soviets and their Polish collaborators. It is estimated that one hundred and tens of thousands of people passed through its ranks. At its peak, 30,000 people continued their armed activities in Poland in the post-war period. Today we call them the Cursed Soldiers or the Unbroken Soldiers. In other countries of the Eastern Bloc, other terms were used towards those who continued the fight against communism after the end of World War II, most often they were referred to as Forest Brothers.

And it is the remains of the Unbroken Soldiers that are being searched for by the Office of Search and Identification of the Institute of National Remembrance, headed by the professor. Since when has the Polish state been doing such a search?

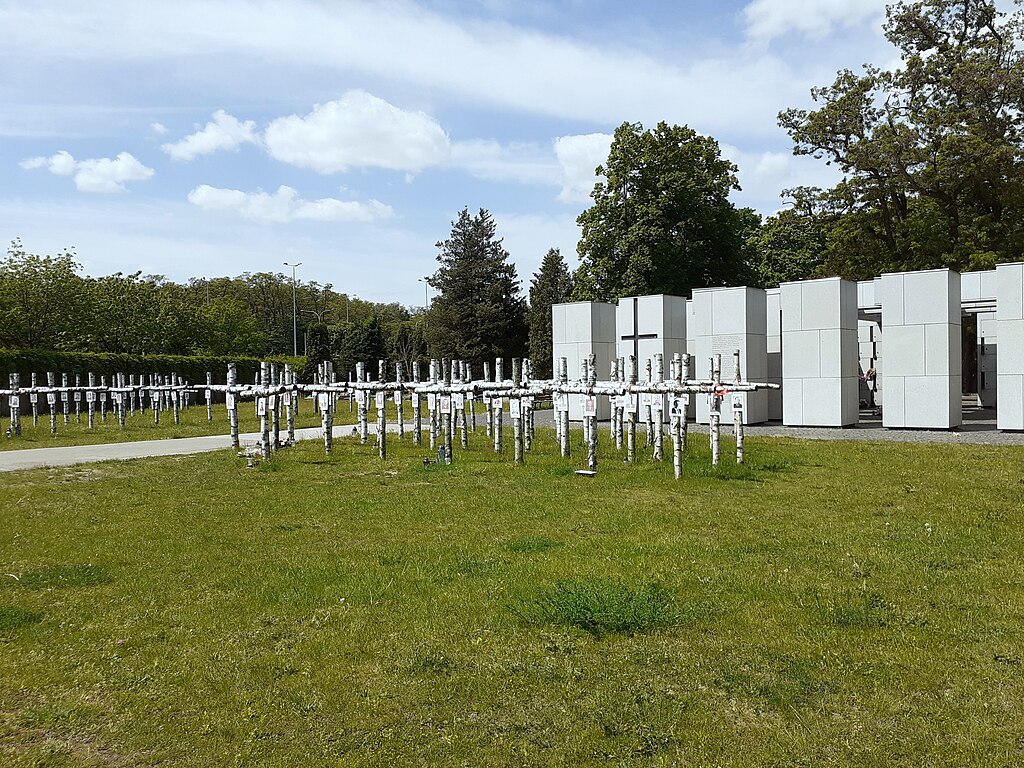

Poland has 20 years of experience in searching for victims of the communist system. In September 2003, the first victim we searched for – a person sentenced to death and executed – was found in the Osobowicki Cemetery in Wroclaw. Subsequently, we expanded our activities to other places, not only in Lower Silesia. This process – filled with many burdens and great challenges, carried out initially by a small group of people – has grown into a venture that today exists on a completely different scale. There are now state, institutional activities, and a special status was given to them in 2016, when the Polish Parliament decided to amend the Law on the Institute of National Remembrance, establishing a special Search and Identification Bureau of the Institute of National Remembrance within the INR. It outlined the timeframe and the duties that the office should carry out. The Polish parliament stated that our task is to search for, find, research and personally identify Poles who died fighting for Poland’s freedom, who were murdered by Poland’s various oppressors, various occupiers between 1917 and 1990. Our task is to find those who were murdered by the Bolsheviks, Germans, Communists, but also by Ukrainians. Knowing Polish history, the scale of the dramas that befell us in the 20th century, the scale of the murders carried out, we are aware that the task we have undertaken must be carried out for many years to come. This is not a challenge that can be met in a single generation. But it must be said that in recent years, since the establishment of the Bureau, a great deal has been done. Throughout Poland and abroad, in Lithuania, Belarus, Germany, we have found the remains of about two thousand victims. We have examined more than 300 sites where we have carried out prospecting, archaeological work. Every year, we conduct search operations and exhumation works at dozens, sometimes as many as seventy, sites.

How are these sites identified? What does the search process look like from start to finish?

Our work is a very long and arduous process, which consists of a number of stages. It starts with information about specific events. Sometimes these are witness accounts of the killings that took place. Sometimes families ask us to determine the burial place of their loved ones. Sometimes, although much less often, it is a single document that leads us to the right track. At the same time, it should be remembered that those who carried out these murders years ago did not document their crimes. On the contrary, the evidence was obliterated. We use the entire spectrum of activities. We use modern sources and tools, such as satellite images or even the analysis performed by, for example, the Lidar system.

And the field work begins.

When we decide that there is a need to make a local inspection and determine activities of a prospecting nature, then an archaeological team with the participation of our anthropologists begins work. When we come across human remains, our specialists begin on-site research. The remains are documented, described and subjected to further medical examinations to determine the type of death inflicted, to confirm whether the person may have been abused before death, subjected to forbidden investigative methods. Each time we collect genetic material, which is used to make an identification. To make it possible, we collect DNA from the families of victims scattered around the world. An extremely important tool for our work at this stage is the CODIS system for genetic identification, which we acquired from the United States. This is a very modern tool, developed by the FBI and used in the United States for identification in the field of modern forensic science.

And once the identification takes place?

Once or twice a year, always in a dignified place such as the Presidential Palace, we hold identification conferences, which have already become state events. There, we present the names, surnames, portraits, and biographies of those we have found and identified, and the families of the victims receive official documents from us stating that their loved ones, for whom a trace disappeared many years ago, have been found, identified and can be buried. Ceremonial funerals of a state nature, with military ceremonies, are the final stage of our work. Funerals that should have taken place years ago, but which never did. This is how Poland fulfills its duty to its citizens murdered in the 20th century.

The Bureau’s team consists of specialists in many different fields, but you emphasize the importance of involving volunteers in the process. What is their role?

From the very beginning, i.e. from the first search in Wroclaw, we were convinced that the implementation of such a research process would not be possible without the creation of a team consisting of specialists in various fields of knowledge: archivists, historians, archaeologists, forensic medics, etc. We built such a team, which now consists of more than 70 specialists working in Warsaw and in every provincial city where there is an INR branch. From the very beginning, we are accompanied by a multitude of volunteers who work with us in Poland and abroad. In every place where we are. This is a mass phenomenon that has been going on for years and is not waning. To illustrate this, I will use the example of the activities at Łączka in 2017, when more than 250 volunteers worked with us in two months. And this is just one site and only two months. These are people of different ages – from youth, teenagers to 70-year-olds. People of different professions. There are students, and civil servants, and musicians, and politicians, and priests, and people who do manual labor every day. This shows how important for many Poles are the activities carried out by the Polish State and on its behalf by the INR’s Office of Search and Identification. How many Poles consider it an honor and a privilege to take part in the search for Polish heroes.

Reading the memoirs of the families of those murdered by the Communists and never found shows how great the pain of not knowing the fate of loved ones can be. How important it is to know the place of burial, to be able to stop by the grave, light a candle, say a prayer. Many years have passed, successive generations have come. For the families of Poles found by the Bureau, is this still a matter of such great importance?

It is important to know and remember that many thousands of Poles could not bury their loved ones, say goodbye, weep over the grave. This situation lasted for decades and it is still alive in families. Every case of finding a victim – I repeat, every case, whether we are talking about a victim of German, Soviet, Communist or Ukrainian crimes – means for families to live to see the moment they have been waiting for for several generations. Someone who doesn’t know Polish history, doesn’t know how many Poles hope to live to see the moment when their loved ones will be found, buried with honor, when they will be able to say goodbye to their loved ones in person in a solemn Mass, someone who doesn’t know this will never understand why we Poles so often return to our history, why we are so sensitive to it. Precisely because the wounds inflicted years ago still have not healed. When we find and identify the victims, and their loved ones are able to say goodbye to them, a kind of peace returns to these families. And every such moment is a hope for those who are still waiting, that maybe someday, maybe in six months, maybe in a year, or maybe in a few years, they too will live to see the moment when their loved ones are identified and properly escorted to their eternal resting place.

The number of those who are still waiting is enormous. Probably impossible to estimate.

Let me use just one example. The example of the Volhynian massacre committed by Ukrainian nationalists against the Polish population during World War II. According to various sources, between 140,000 and as many as 200,000 people were murdered then. And this is just one of the really many tragic events from Polish history, when the numbers of victims are counted in tens or hundreds of thousands. This is a huge scale and a huge task facing the Polish State. But this task is being carried out. And it will be carried out. I am convinced that no matter who will come to hold power in Poland in the future, whatever political fraction, there will be no one who will say that this process is not worth pursuing, that there is no need to return to the past, that the search should be stopped. I am convinced that no one will choose to do so, and this process will be carried out by us as well as the generations that will come after us.