Europe’s strangest newspaper chasing right-wing dissidents in Poland

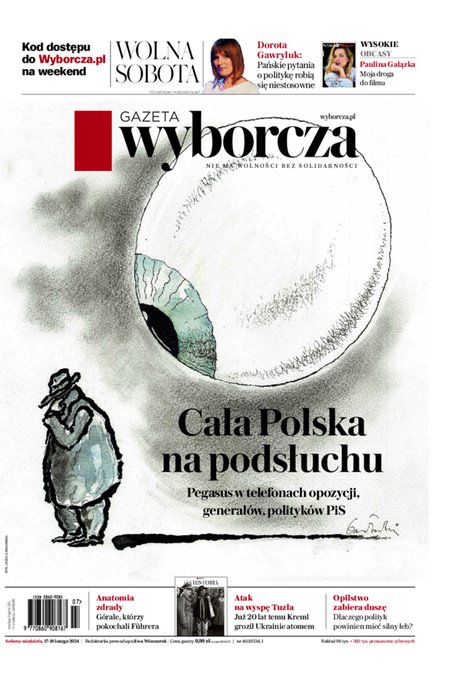

Is there any other major European newspaper that would engage in political purges as such a boon companion of the government it supports? Examples from the recent spate of political lynching of people unlucky enough to have worked in ordinary government institutions or public media under the governments of Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland reveal the role that Gazeta Wyborcza has been playing, and not just since yesterday. How did Adam Michnik’s daily, of which George Soros’ foundations are now a stakeholder, come to take on this unique role? And how, after all those years, can it still be seen as a reliable source of information on Poland by the mainstream media in Western Europe and North America?

By Piotr Semka

“‘Thank you and goodbye, ladies and gentlemen.’ An enormous turnover of staff will roll through Poland as the democratic opposition assumes power. In line to lose their jobs are people who – although they worked in public institutions – were first of all dedicated Law and Justice propagandists. Who are these people? Gazeta Wyborcza’s reporters present them in a series titled ‘Thank you and goodbye, ladies and gentlemen.’ Is anyone missing from our list? Please let us know…”

In all local editions of Gazeta Wyborcza on October 21, 2023, the same headline heralded articles that represented something new, even for the brutal standards of the political fight of the past 20 years. Here, a daily newspaper was stepping into the role of an institution preparing lists of names of people for dismissal. What is more, the list was headed by people who, due to the change of government, would have to leave their jobs anyway, such as provincial governors, provincial conservators of historical monuments, museum directors, or chief executives of state-owned companies – people whom the new government would normally be expected to replace at some point anyway.

And yet Gazeta Wyborcza, in all of its local supplements, decided to join in pointing the finger at those who were to be fired, and publicly stigmatized as well. Before they went, they had to be presented to the masses as ‘Law and Justice propagandists.’ Not as officials who have performed administrative functions well or badly, but as deserving of contempt.

Adam Michnik is the founder of Gazeta Wyborcza and its editor-in-chief. He has many times harked back to the events of March 1968 as his most terrible memory. When Michnik wants to emphasize his horror at some event, he uses the phrase ‘March is still haunting me.’ Interestingly, proposing a list of people for removal from their jobs, or encouraging his readers to send their suggestions for more dismissals, did not in any way remind the man in charge of Gazeta Wyborcza of communist purges. March ‘68 was indeed a time of when, both in propaganda newspapers and at party meetings, the names of people to be removed from their positions were called out. In the years 2015–2016, as Law and Justice was saying goodbye to many appointees of the preceding political configuration, nobody came up with an idea in the style of ‘Thank you and goodbye, ladies and gentlemen.’

And as Gazeta Wyborcza does that now, it arouses no objections from intellectuals or even commentators in other media outlets. Gazeta Wyborcza can camouflage this type of revolutionary zeal with terms such as ‘making order’ or cleaning up after Law and Justice with an ‘iron broom.’ I am not aware of any other major European newspaper that would engage in political purges as such a boon companion of the government it supports.

And now for another example of action by Gazeta Wyborcza that is unprecedented among European daily newspapers. Following two potentially controversial statements from Republika Television, a number of companies announced withdrawal of their commercials from the channel. Most newspapers and media portals reported on this decision made by those few companies, striking a serious tone. However, Gazeta Wyborcza went much further.

On January 13 it published an article headlined “Here are the companies still advertising on TV Republika. Zygmunt Solorz and Lidl top the list.” The authors – Leszek Kostrzewski and Piotr Miączyński – began their piece as follows: “Although many companies have announced withdrawal from Tomasz Sakiewicz’s Station, there is still a large number that do not intend to do so. And it is not a case of state-owned companies still controlled by Law and Justice, but private and foreign firms. Here is the list.”

Again, one may wonder whether any other newspaper assumes the role of a watchdog checking on which companies still dare not to withdraw their commercials from Poland’s only remaining right-wing news channel. The tone of that article is distinctive. It is not just about giving facts. This is a list proclaimed by irritated controllers, who clearly want to exert pressure on those who still have not withdrawn from a television channel that is stigmatized for incorrect thinking.

There are many more examples of such behavior, as Gazeta Wyborcza alternates between a controlling function and one of stigmatizing people whom it views as tainted with some dishonorable activity. (…) These two examples taken from the recent spate of political lynching of people unlucky enough to have worked in normal government institutions or public media reveal the role which Gazeta Wyborcza has been playing, and not just since yesterday. How did Adam Michnik’s daily newspaper come to take on this unique role? Whom does it consider its enemies? Where does the determination it shows in such actions come from?

Foreign money and pressure is artificially pumping up the LGBT movement in Poland

A newspaper like no other

It is hard not to attribute the origin of this peculiar notion of journalism to the epoch when Adam Michnik was a post-Marxist dissident in the Polish People’s Republic, belonging to the group of dissenters of March 1968, and next to the democratic opposition under the rule of Gierek and Jaruzelski. Particularly in the years 1968–1980, the so-called commandos, who had come out of prison after the March sentences, found themselves in a social vacuum. They had difficulty finding jobs, were under nonstop surveillance, and were shunned by many as lepers. Some people avoided them because of their ties to the communist system; others out of simple fear.

To survive and to stress their moral legitimacy in speaking out on public matters, Adam Michnik and his friends had to emphasize very strongly the immorality of the actions taken by the communist authorities, while contrasting them with their own support for democracy, tolerance and truth. In those years, which were not easy for the opposition, only such an attitude made it possible to live through the hardships of repression and attacks in communist newspapers, on the radio, and on television. The problem is that the situation pushed Adam Michnik and his consorts into the habit of assuming the role of a moral prosecutor, and made them prone to divide people into those who fully accepted their current line of thought and those who for some reasons were opposed to it.

Opposition activists with different leanings, especially those in conservative or independence-oriented groups such as the Confederation of Independent Poland (Konfederacja Polski Niepodległej, KPN) or the Young Poland Movement (Ruch Młodej Polski, RMP), experienced just how painful this division into those in the right and those in the wrong could sometimes be. In cases of differences of opinion, Michnik moved very easily to wondering whether his opposition competitors were perhaps not agents provocateurs of the regime’s secret police (as in the case of KPN leader Leszek Moczulski) or anti-democratic nationalists or xenophobes (in the case of RMP activists).

These vices of Adam Michnik revealed themselves even more after the election of June 1989, when political pluralism slowly began to develop in Poland. Michnik retained the mannerism of portraying his opponents not as people having different opinions, who should be respected, but as morally base characters. When Lech Wałęsa, as the leader of the Solidarity movement, decided that Michnik should be Gazeta Wyborcza’s editor-in-chief, this appointment seemed to be merely a practical one, aimed at helping Solidarity to win the first partially free elections [Gazeta Wyborcza is Polish for ‘electoral newspaper’, ed.].

Polish daily newspaper Rzeczpospolita in the service of chaos after Soros takeover

With the communist authorities’ consent, however, this newspaper, originally planned for the election campaign, transformed into the first Polish daily that, while still censored, was placed beyond the communists’ control. Michnik quickly discovered that possession of such an instrument gave him incomparably greater influence on political life than being a politician. He therefore felt no regret in renouncing his Upper Silesian parliamentary seat for the Citizens’ Parliamentary Party (Obywatelski Klub Parlamentarny, OKP), and deciding instead to focus on building his own political organ.

And it is certainly accurate to call it ‘his own.’ Instead of patiently presenting the different views within Solidarity, Michnik turned the newspaper into a media outlet of the secular left. The Solidarity Trade Union voiced its indignation in vain, and removed the Solidarity logo from the daily. Michnik now had his own distinctive media outlet. His work, combined with that of all his team, as well as his outstanding editorial talent, brought about the rise of the strongest daily newspaper on the market. And for years to come he used it as a tool for launching his political plans, for contending with those he considered enemies, and for somehow taming the Polish elites and intellectuals so that they would think in the terms he outlined. (…)

Adam Michnik adopted the role of some kind of herald of a holy war of good against absolute evil. (…) And if you are fighting against the ‘worst villain,’ then even the most brutal methods are justified. (…)

This article was first published in Polish in the Do Rzeczy weekly in February 2024.

The author is a well-known conservative journalist and columnist in Poland, having worked for many prestigious media outlets since the fall of communism in Poland in 1989–1990. He was a dissident against the communist regime in his youth in the 1980s, when he took part in students’ protests and wrote for Solidarity’s underground press.