Genocide Prevention by One Polish Condottiere

Gan Ganowicz’s dream of falling in battle against the Communists was never fulfilled. But he did prevent genocide in at least two places.

Genocide prevention is about neutralizing regimes and groups fostering mass murder through their ideologies and actions. In the West, most conceptualize genocide prevention in terms of education, lobbying, and humanitarian assistance. Recently, under the auspices of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, prominent Americans even created a useful blueprint for genocide prevention. Hopefully, the new administration will pay heed. Meanwhile, people are dying and even the best “road map” can’t stop it fast enough. But I knew someone who did in Congo almost 50 years ago.

Rafał Gan Ganowicz (1932-2002) came from a Muslem Tartar family which found refugee in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 16th century, converted to Christianity, and served its adopted nation in every war and insurrection. Rafał was seven years old when Hitler and Stalin jointly invaded Poland. The Germans killed his mother during the siege of Warsaw in September 1939. When Rafał was 12, his father, an officer in the pro-Western clandestine Home Army, fell in the Warsaw Rising in August-September 1944. The boy also participated in the anti-Nazi struggle, fled from a German concentration camp, and hid until the arrival of the Soviets in January 1945. Afterwards, Rafał continued his affiliation with the pro-Western underground.

Enemy of humanity

According to Gan Ganowicz, with the Nazis annihilated, it was one’s duty to defeat the other enemy of humanity: the Communists. He resented the rapine and pillage of the Red Army, as well as the terror and violence of the Soviet secret police and its local Polish proxy. His clandestine team consisted often of war orphans like himself. They operated in Warsaw, which was destroyed in about 80%. At first, like under the Nazi occupation, Rafał’s youth secret outfit limited itself to propaganda. The boys and girls distributed underground leaflets, defaced Communist posters, and painted anti-Soviet graffiti. The Stalinist secret police began shooting at the Warsaw taggers. They fired back in night time engagements in an impenetrable sea of ruins.

Finally, in 1950, the secret police tracked Rafał down. Warned at the last second, he headed straight for the Warsaw train station. Clutching two guns, the eighteen year old freedom fighter hid under a train carriage and traveled undetected to Berlin. After having been vetted and quarantined for three years in Germany, US armed forces intelligence transferred Rafał to France. He attended a commando training course and, simultaneously, an officers school of the Free Polish Armed Forces in Exile. This was a joint clandestine operation of the US government and the émigré Polish government in London. Upon graduating, Rafał was commissioned second lieutenant in the Polish army and deployed with the US Army guard companies. He was slated to be parachuted into Soviet-occupied Poland during the apparently imminent liberation of central and eastern Europe. Alas, Operation Rollback never materialized. Following the ill-fated insurrection in Hungary in 1956, and the subsequent thaw in US-Soviet relations, the commando teams were disbanded. Undeterred, Rafał vowed to continue to fight the Communists as soon as the opportunity presented itself.

For the next few years, the ex-commando worked as a high school literature teacher in France. In 1965, having heard about the atrocities in the Congo, he volunteered to fight on the side of Moses Tschombe whose enemies were backed by the Kremlin. The conflict in the Congo stemmed from the sudden retreat of its colonial master, Belgium, and the concomitant collapse of law and order.

Mass slaughter followed of genocidal proportions. Rebellions and revolutions multiplied. The realm became not only a Cold War battlefield, but also a jousting ground for would-be strongmen and warlords as well as centrifugal regionalists and ferocious tribes battling all and sundry.

Fleeing Cubans

Lieutenant Rafał Gan Ganowicz fought with his battalion in eastern Congo in defense of Stanleyville (now Kisangani) and later operated between Katanga and Kivu. His troops were the bellicose Katangans under the command of a handful of Western NCOs and officers. First, they defeated the revolutionaries of the Red Chinese-trained Pierre Mulele and the Cuban-supported Gaston Soumialot, capturing the Soviet-educated Mchawi Masutu “Mkundu” in the process. Ultimately, the government contractors commanding the troops of Tschombe routed Che Guevarra himself and forced his Cubans to flee.

Next, the units under Gan-Ganowicz operated to restore peace and order and pacify the countryside. The task was daunting not only because of the Communist revolutionary factor but also because some of the locals reverted to their own savage ways. In some instances, their Marxist leaders duped and doped their revolutionaries who, consequently, believed themselves to be invulnerable to bullets only to be mowed down by the hundreds in futile human wave attacks. In the most shocking case of savagery, a tribe of cannibals, so-called “people crocodiles,” descended upon the peaceful fishermen of M’Wabu by the Lualaba River. The cannibals kidnapped and ate their victims, decorating their camp-site with the heads of the unfortunates. The Polish officer sent out his troops to hunt the murderers down and kill them.

At this point, order, any order, meant a halt to the massive bloodletting. Crushing the revolution and stomping out savagery meant saving lives in a short run. In a long run, law and order could have ushered in a just peace and a wholesome political system. Alas, they still continue to elude the Congo. And they are also absent in Yemen, Rafał’s next destination, where he traveled in 1967 as a government contractor for the King of Saudi Arabia.

Warrant for genocide

In Yemen Gan Ganowicz trained the tribal insurgents; he fought the Egyptian national socialists auxiliaries of the Kremlin; and, last but not least, he targeted Soviet advisors and other assets. His notable scores include downing the MiG of the head of the Red Army’s military mission in Yemen; obliterating a convoy of Soviet tanks in a mountain canyon ambush; and leveling the Soviet Embassy there with his mortars. The Polish officer accepted the Saudi government contract because he knew that anywhere the Communist revolution prevailed there resulted oppression, terror, and, often, genocide. After all, the Communists promised to exterminate the old elites and anyone connected to tradition to usher in their millenarian utopia. Class struggle, like race struggle, is a sure warrant for genocide.

By the end of the 1960s, Gan Ganowicz was back in Paris. True to his rule to fight only against the Nazis and Communists, he turned down several jobs that failed to fit his ideological profile. This included a request from Fidel Castro to enlist in one of his revolutionary undertakings; and a few proposals from his old commanding officer Bob Denard to overthrow this or that African government. The Polish officer refused to be involved, although he did seriously considered going to Cuba to assassinate Castro.

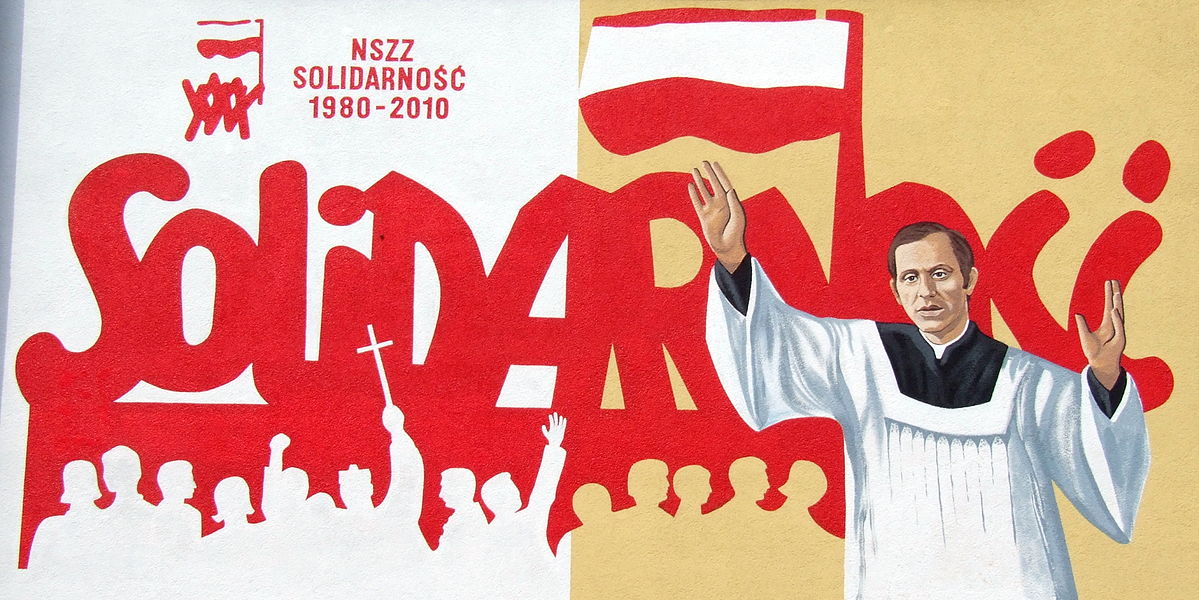

In the late 1970s Rafał began working as a journalist for Radio Free Europe. When the Communists imposed martial law and crushed Solidarity’s national liberation movement, he became the chief coordinator in the West for the movement’s most radically anti-Communist wing: the Fighting Solidarity. In the mid-1980s Gan Ganowicz also agreed to serve as a commanding officer of a CIA-backed Polish Legion to fight in Afghanistan. I know that because I volunteered to serve under him but was sorely disappointed when the project was scrapped. The Afghans received the Stingers instead. And that is how I never became a government contractor.

After 1989, friends convinced Gan-Ganowicz to visit Poland. In the mid-1990 he became a mini-celebrity in the student anti-Communist circles. Polish TV made a documentary about his life. The neo-Communist and liberal powers-that-be vainly attempted to thwart its screening. There was even a leftist media campaign against him, depicting him falsely as a money-hungry bloody mercenary. By the end of the 1990s Rafał moved to Poland permanently and died there soon after of cancer. He left behind a memoir aptly titled Kondotierzy (Condottieri), “Soldiers of Fortune.” Gan Ganowicz’s dream of falling in battle against the Communists was never fulfilled. But he did prevent genocide in at least two places.

Marek Jan Chodakiewicz

We thank prof. Marek Jan Chodakiewicz for sharing this article.